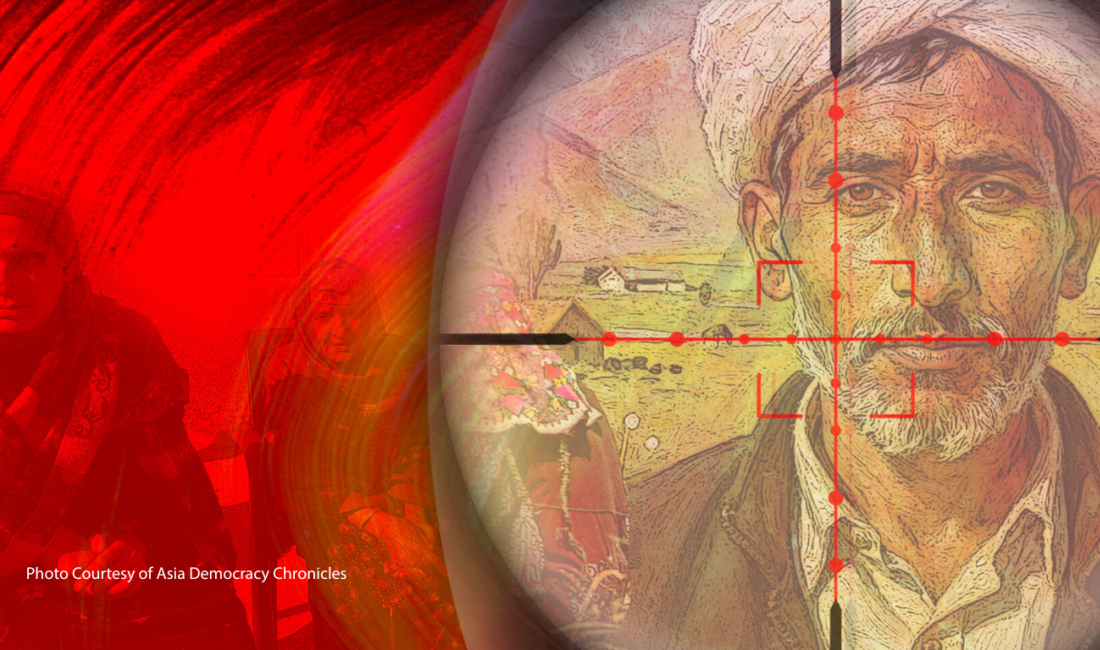

Modi Turns on Tribes Once Considered the Indian State's Eyes & Ears in Contested Kashmir

This illustration and story were produced and published by Asia Democracy Chronicles.

On Aug. 9, 2020, three families from Rajouri district in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) in northern India arrived at a police post to report missing sons. Each family had a son they had not heard from in weeks.

The three sons – 20-year-old Imtiyaz Ahmad, 16-year-old Ibrar Ahmad, and 25-year-old Mohammad Ibrar – had said that they would be looking for work in southern Kashmir, about 160 kilometers away from their homes.

After their visit to the police, the families waited anxiously for news. A few more weeks passed before pictures of three “unidentified terrorists” emerged on social media. According to the Indian Army, the “terrorists” were killed in a gunfight in Amshipora village, in Kashmir’s Shopian district. But it was later revealed to be a fake encounter; DNA tests also showed the “terrorists” to be the missing sons.

All three belonged to the Gujjar-Bakarwal community, Kashmir’s largest tribal group and long regarded as India’s most trusted allies in the conflict against what New Delhi says is Pakistan-backed militancy. Their killings marked a breaking point in a decades-old bond.

“When my son went missing, I imagined many terrible possibilities but never that the Army could be involved,” said the father of one of the murdered youths. “We live in a border area and have always stood by the Army whenever they needed us. But in the end, my son was killed by the same army I trusted. What wrong had he done? Have we become a threat now?”

The “Amshipora fake encounter,” as the case was called, was no isolated incident. In fact, it was part of what many in the community now see as a sustained pattern of state violence and persecution against the Gujjar and Bakarwal since 2014.

Although they are nomadic herders spread across J&K, the Gujjar and Bakarwal have especially significant numbers in Kashmir’s Rajouri and Poonch districts. These are near the heavily militarized Line of Control (LoC), which divides Kashmir between India and Pakistan. The Gujjar and Bakarwal are estimated to make up some 20 percent of J&K’s population of 13.6 million.

While also predominantly Muslim, they are distinct from the Kashmiri-speaking Muslim majority of the Valley. The Gujjar-Bakarwal have historically maintained a different relationship with the Indian state as well. When Kashmir turned into a constant flashpoint following the 1947 partition of British India, subsequently seeing an armed uprising erupt in the 1990s, the Gujjar-Bakarwal largely aligned themselves with New Delhi.

They became one of the Indian state’s most valuable local allies, with many of them guiding and providing intelligence that helped reclaim territory from militants who had gained control of remote mountain belts.

“Where do I even begin to count the sacrifices our community has made for India?” said a 60-year-old tribal activist who joined security forces in counterinsurgency operations during the early 2000s. “It was with the Gujjar’s help that militancy was wiped out from this region, though we paid a heavy price for standing up to militants.”

But their bond with the central government has steadily deteriorated, particularly in the last six years. Among the Gujjar and Bakarwal communities, an intense sense of alienation and mistrust now prevails. The pervasive fear of shifting state policies, coupled with the feeling of betrayal by the central government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has fractured a relationship that has historically been considered strategically vital for India.

A Lengthening Bloody Trail

In November 2023, the Gujjar-Bakarwal could only watch as an Armed Forces Tribunal suspended the life sentence of the Indian Army captain found guilty of abduction and murder of the three young men in Amshipora; he was also granted bail.

Weeks later, militants ambushed army vehicles in Poonch district, killing four soldiers. The next morning, the Army’s anti-terrorism unit detained several villagers from a small Gujjar hamlet near the ambush site.

Residents had described their village as “a second home” for the Army. Yet by that evening, three of the detained villagers were dead. Videos that surfaced online showed soldiers beating detainees and pouring chilli powder into their wounds.

“My son’s body had burns and blackened marks from severe beating,” said 57-year-old Wali Mohammad, whose son was among the dead. “We have never supported militancy. We stood by the Army. Is this the price of loyalty?”

“They knew everyone by name,” said Noor Ahmad, a Border Security Force constable whose brother was among those killed. “Our people would make them tea and bread. Now that bond is broken forever.”

The violence against the Gujjar-Bakarwal continues, however.

Last February, Makhan Din, a 25-year-old Gujjar, recorded a video moments before killing himself by drinking insecticide. In the video, he alleged that he:

“was beaten until I lied that I had seen militants.”

Police denied the claim, saying Din was only questioned about “suspicious Pakistani contacts.” But his father, Mohammad Murid, told Asia Democracy Chronicles (ADC) that both of them were beaten at a police station.

“They separated us,” Murid said, “and I could hear Makhan’s cries from another room. He killed himself because he couldn’t face it again.”

Din’s suicide has become emblematic of the fear and despair gripping the community, while deepening the perception that India’s once-loyal tribal allies are now being collectively punished.

Indeed, just two months after his death, three more Gujjar youths were found dead in a canal in south Kashmir. The police said they drowned; their families alleged torture and murder.

Last July, another Gujjar youth was killed in what police called an “encounter” in Jammu. His family said it was staged.

“Sinister” Changes?

For the Gujjar-Bakarwal community, the violence has become intertwined with another set of crises: evictions and dispossession.

Since 2014, when Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) first came to power, eviction drives targeting forest-dwelling Muslims have intensified, especially in Hindu-majority Jammu. In 2016, a Gujjar youth was shot dead during an anti-encroachment operation in Jammu’s Samba district.

The most horrifying attack came in 2018, when an 8-year-old Bakarwal girl was abducted, gangraped, and murdered in Kathua, also in Jammu. BJP members openly supported the accused, triggering nationwide outrage.

Tribal leaders said the crime was meant to drive the Bakarwal out of the area. Since then, hundreds of Gujjar and Bakarwal families have received eviction notices branding their shelters as “illegal occupation” on forest land. In many cases, bulldozers razed their homes while residents watched helplessly.

Mehbooba Mufti, former chief minister of the erstwhile state of J&K, called the campaign part of a “sinister agenda” to displace Muslims.

“These people who have protected forests for centuries are being evicted illegally,” she said. “A drive has been launched to demolish their structures and harass families. Who do they intend to sell the forest land to?”

While the Indian Forest Act of 1927 allows such state power, the Forest Rights Act (FRA) of 2006, which should protect tribal dwellers, remains poorly implemented in J&K. After Article 370’s abrogation in 2019 that had Jammu and Kashmir losing its special autonomous status and splitting the region into two Union Territories (J&K and Ladakh) under direct central control, both laws were fully extended to the region. But evictions still continued.

Then last year, New Delhi decided to expand the Scheduled Tribe (ST) status to the politically influential Pahari community. The Gujjar and Bakarwal were outraged. India’s Constitution acknowledges Scheduled Tribes as historically disadvantaged and entitled to affirmative action in education, employment, and political representation. Recognized as STs in 1991, Gujjar and Bakarwal had gained long-overdue access to education and jobs through reservation quotas. They now fear those benefits will be diluted by the inclusion of more privileged groups.

“This reservation is an assault on our community in multiple ways,” said prominent Gujjar activist Choudhary Talib Hussain. “Until now, some of our children could hope for jobs or education through the ST quota. But including new groups who don’t even meet the basic criteria of being tribal destroys that fragile chance.”

“They’ve gone as far as including upper-caste Brahmins,” he added. “These are the people who already dominate India’s bureaucracy and economy. How can they be put on the same level as Gujjar-Bakarwal, whose first generation is only now accessing basic education? This move has made us more marginalized than ever."

Power and Losses

To political analysts, this and other changes are part of the BJP’s strategy to consolidate electoral power in Jammu and Kashmir.

“There are two key factors since 2014 when Modi came to power,” said a Kashmir-based political expert. “First is the anti-Muslim sentiment shaping policies. The second is that outside Hindu-majority Jammu, the BJP has struggled to gain influence in tribal belts.”

“To make inroads, the party has empowered groups that are not solely Muslim, but also include Hindus and Sikhs,” the analyst continued. “This approach has strengthened BJP’s vote bank, but in doing so, it has sidelined those who stand in the way, particularly the Gujjar and Bakarwal communities, who have borne the brunt of this political consolidation. These policies may not be explicitly anti-Gujjar, but they have nonetheless turned the community into victims of the larger political design.”

Yet for all the suffering the Gujjar–Bakarwal are being made to endure, observers say the ultimate loser may be the Indian state.

In recent years, Pakistan-backed militants have shifted their operations from the heavily guarded Kashmir Valley to the relatively peaceful Jammu region. Experts say these militants are better trained and more strategic.

Since 2021, the Pir Panjal range–dominated by Gujjar-Bakarwal villages–has become a staging ground for targeted attacks. There is a discernible unease about the attacks and gunfights widening to other districts that have remained militancy-free for decades.

In June last year, militants opened fire on a bus carrying Hindu pilgrims in Reasi, causing it to plunge into a gorge. Nine people, including a two-year-old child, were killed, and over 40 injured. The attack ended two decades of peace in the district. Authorities alleged that a local Gujjar man provided the attackers logistical support.

Last April, militants killed 26 civilians – all Hindu pilgrims with the exception of one local Muslim pony operator – in Kashmir’s tourist station, Pahalgam. India’s premier anti-terror agency later arrested two men, who it accused of helping the attackers with food and shelter. Both are allegedly from the Gujjar-Bakarwal community.

A retired police inspector general commented:

“A decade ago, this community would guide security forces through the toughest terrains. Today the same people have turned away because the state has waged a war on their minds and existence. What message is being sent when the only Muslim tribal group in these areas feels under attack?”

A former Indian Army commander who has served in the region conceded that alienating the Gujjar-Bakarwal weakens India’s counterinsurgency capabilities.

“To fight militancy, especially where foreign terrorists are involved, local support is critical,” he said. “If the trust between Gujjar-Bakarwal and the army weakens, it will be harder to gather intelligence and control these areas. The government must urgently rebuild that relationship.”