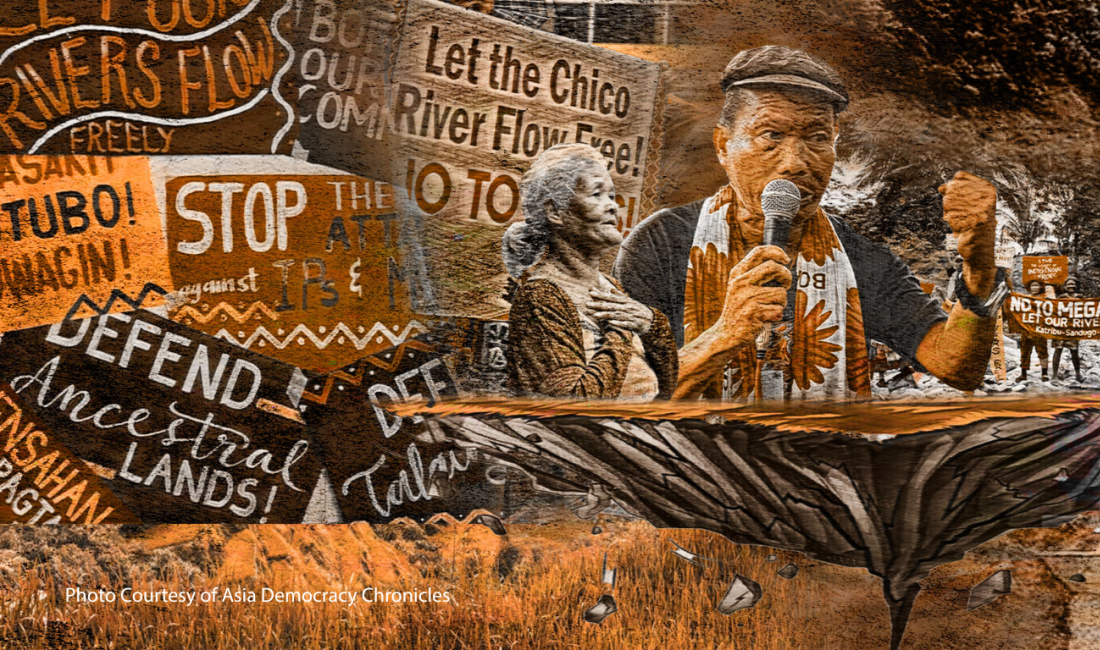

Indigenous People in the Philippines Battle Over Control of Their Lands

This essay and accompanying art were produced and published by Asia Democracy Chronicles.

It is not expected to be completed until December next year yet, but the Jalaur River Multi-Purpose Project Stage II (Jalaur Dam) is already being counted on by the Philippine government officials to bring numerous benefits — including year-round irrigation, bulk water supply, hydroelectric power and an ecotourism boost — to the central Philippines. It also happens to be the first large-scale water reservoir in the Visayas, one of the country’s three major island groups.

The Jalaur River for the People Movement (JRPM), however, views the PhP11-billion ($197 million) project as both an environmental threat and a violation of indigenous peoples’ rights. Jalaur River holds immense cultural importance to the Tumandok of Calinog, Iloilo and Tapas, Capiz, whose burial and sacred sites dot the 123-km waterway.

JRPM coordinator John Ian Alenciaga says that resistance to the project, which has experienced allegations that include “procedural lapses, manipulations and deceptions in the free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) process, militarisation of communities and outright violence against those opposing the project,” spans decades.

Elsewhere in the Philippines, similar struggles are taking place. In Luzon, the country’s biggest island group, indigenous communities are resisting large-scale corporate and government projects on their lands. In Southern Tagalog, the Dumagat are protesting against the Kaliwa Dam, which threatens to submerge nearly 2,500 households. In the north, indigenous groups in Apayao and Kalinga face similar projects, while Isnag-Yapayao communities in Ilocos Norte contend with wind and solar farms.

Land conflicts involving indigenous territories are also prevalent in Mindanao, the Philippines’ third island group. In Zamboanga del Norte, the Subanon oppose a nickel mine, citing watershed risks. In Bukidnon, a banana plantation encroaching on indigenous land regularly has aerial spraying that allegedly pollutes nearby water sources. In Maguindanao, a 3,566-hectare mining zone, land grabs and university expansion are displacing the Teduray and Lambangian.

While some oppose these ventures due to their environmental and social impacts, others focus on securing a fair-consent process that guarantees community benefits. Across these cases, violations of the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA) have been reported, including FPIC manipulation, corruption, threats, coercion and violence against opposition groups.

Indigenous rights and global standards

Based on figures from the 2020 government census, the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) says that the Philippines has 9.84 million indigenous peoples, who make up 9.1 percent of the country’s population of 108.67 million. While most indigenous communities are in Mindanao, the Cordillera in Northern Luzon is the only region where they form the majority.

The NCIP is tasked with enforcing IPRA, heralded as a world first in providing a comprehensive legal framework to promote and safeguard indigenous peoples’ rights. IPRA was passed in 1997—a decade before the United Nations adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

The UNDRIP sets minimum standards for recognising, protecting, and promoting indigenous rights, prohibiting discrimination, affirming their right to maintain distinct identities, and supporting their participation in decision-making. To date, however, both UNDRIP and IPRA seem to have been largely ignored by state and corporate actors in the name of development.

In a 2007 message, then UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues Chairperson Victoria Tauli-Corpuz described UNDRIP’s adoption as the start of the “challenge to ensure the respect, protection and fulfilment of indigenous peoples' rights.”

“We foresee that there will be great difficulties in implementing (UNDRIP) because of lack of political will on the part of the governments, lack of resources and because of the vested interests of the rich and powerful,” she said.

Although her words proved prescient, Tauli-Corpuz may not have anticipated that nearly two decades after she made her remarks, indigenous communities worldwide would still be grappling with poverty and face threats of displacement as government and corporate interests intrude on their territories.

According to a May 2024 World Bank report, “the estimated 476 million IPs worldwide account for nearly 19 percent of all people living in extreme poverty today.” The International Labor Organization meanwhile, has underscored inconsistent recognition, limited consultation, land insecurity and unequal access to essential services in 10 Asian countries. A 2023 report of the UN Special Rapporteur on Indigenous Peoples also noted that “green financing” initiatives have failed to provide sufficient resources to protect indigenous peoples from encroachment, attacks and other violence by third parties.

Southeast Asia, in particular, has a troubling record on indigenous rights. Few countries in the region formally acknowledge indigenous communities; fewer still implement protective measures. Indonesia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam rank among the weakest in this regard.

A mere “piece of paper”

In the Philippines, ensuring indigenous rights amid investment-driven development remains a contentious issue despite IPRA. Critics even argue that the law contains loopholes that enable the exploitation of indigenous lands, leading to the displacement of communities and the disruption of their traditional ways of life.

A 2020 review by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies found that while IPRA provides a legal framework for protecting indigenous rights, systemic barriers impede its effectiveness. These include delayed FPIC and ancestral domain protection guidelines, underfunding, and bureaucratic inefficiencies within NCIP.

Cordillera Peoples Alliance (CPA) Secretary General Sarah Dekdeken, pointing to continued violations of ancestral land rights by mining and energy projects, considers IPRA as “just a piece of paper.”

“Worse,” she says, “the FPIC process is frequently manipulated, and our customary decision-making practices are often ignored.”

Dekdeken says that while IPRA provides a foundation for communities to assert their rights, any progress made has been the result of community struggles, not government initiatives.

The core issue is control over their land and resources, which is meant to be a fundamental exercise of self-determination, embodied in the FPIC process.

FPIC is meant to ensure indigenous control over their lands and resources, a process supposed to be built on mutual trust and respect. The law defines it as the unanimous agreement of all members of an indigenous community, determined by their customs, free from external influence, and granted after full disclosure in an accessible language and process. But reports by Global Witness and Amnesty International highlight the lack of transparency and use of threats and violence to pressure indigenous communities into compliance with the demands of the state and corporations.

Global Witness notes that “the military has been linked to the highest number of killings and detentions of land and environmental defenders in the Philippines over the past decade,” with communities experiencing intimidation, harassment and displacement. The country has been ranked Asia’s deadliest for land and environmental defenders since 2012.

Notable cases include the massacre of eight T’boli-Manobo in Lake Sebu in 2018 for resisting a coffee plantation project and that of nine Tumanduk in Panay, two years later, during the campaign against Jalaur Dam. Additionally, two Dumagat activists opposing the Kaliwa Dam were among the nine killed during the so-called “Bloody Sunday” crackdown in 2021 in Southern Tagalog.

NCIP’s role has been scrutinised, particularly due to its involvement in the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict, a state entity notorious for red-tagging. A policy framework has drawn the military into indigenous affairs, prioritising security and resource extraction over indigenous rights.

Isnag resisting the Gened Dams in Apayao, in the Cordillera, even found themselves labelled as communist supporters by the NCIP itself. Isnag-Yapayao leaders in Pagudpud, Ilocos Norte, who opposed a proposed dam project on their land, received a visit from the police.

NCIP has also faced allegations of collusion with project proponents, including “divide-and-rule” tactics to gain consent. The fact that project proponents fund FPIC activities creates a power imbalance, critics say, asserting that this reduces the conduct of FPIC to procedural compliance rather than ensuring genuine consent.

An NCIP insider requesting anonymity also says that political and corporate influence can override indigenous rights.

“It’s not just about corporations funding FPIC activities,” says the insider. “The bigger issue is when your higher-ups advocate for project proponents or when politicians push for projects themselves.”

“When companies can influence politicians and NCIP officials, FPIC collapses,” the insider adds. “Even provincial officers or lawyers who try to assert IPRA can be pressured.”

In a 2019 interview, former NCIP chairperson Zenaida Pawid explained that NCIP was intended to function as an independent agency. Its top officials are appointed by the Office of the President, however, allowing certain executive influence. Moreover, while commissioners have fixed terms and operate as a collegial body, they ultimately serve at the pleasure of Malacañan Palace, making them politically vulnerable.

Missed steps, legal complications

Retired U.S. environmental regulator and advocate Ruben Guieb, for his part, sees the practice of securing community consent before completing the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) as simply wrong. The report is crucial to the FPIC process, he says; without it, the consent process is flawed and uninformed.

The EIA, required under the Philippine Environmental Impact Statement System, serves as the foundation for evaluating projects with potential ecological risks to ensure responsible planning and decision-making. In several FPIC processes he attended, Guieb says, there was no EIA.

“They (NCIP) hold community meetings with no documented information except for the proponent’s word,” he tells Asia Democracy Chronicles (ADC). “It is disadvantageous for the community when this critical study is absent.”

While the FPIC guidelines mention the EIA, its presentation in proceedings is not mandatory. Section 22 of the rules states that proponents may provide the results “if available.”

Worse, some projects begin without FPIC or a Certificate of Precondition. By law, proponents must secure this certificate to confirm proper FPIC before proceeding. At least five projects, however, were reportedly started without an FPIC in Northern Luzon: the windmills in Pagudpud and a solar farm in Burgos, Ilocos Norte; the Chico and Alfonso Lista pump irrigation systems in the Cordillera; and a mining exploration in Abra.

There are also legal limitations that hinder indigenous autonomy. The Regalian Doctrine, for instance, restricts indigenous ownership to surface lands, with the Supreme Court affirming state control over natural resources.

More than half (56 percent) of the Department of Energy’s Competitive Renewable Energy Zones (CREZs) overlap with indigenous territories in the country. Mining policies continue to clash with indigenous tenurial security as well, exacerbating land conflicts. Over the last three decades, indigenous peoples in the Philippines have lost land larger than Timor-Leste to mining projects—or a fifth of their delineated territory, which includes approved and pending ancestral domains as of May 2024.

Further complicating matters are laws like the Energy Virtual One-Stop Shop Act that have streamlined permitting processes for projects on indigenous lands, imposed strict timelines on FPIC proceedings, and limited grounds for denial. There is also the “Green Lanes” initiative, which may ease business transactions at the expense of indigenous peoples’ rights.

There are ongoing efforts to revise FPIC guidelines. But these have drawn criticism from 68 organisations, which warn that the proposed changes “contain provisions that seriously reduce, undermine, and violate the rights of indigenous peoples in decision-making.”