Children do not start wars, but they pay the highest price for them.

They are a part of society without a say or role in decision-making, yet in situations of war and instability, they are often forced to take on responsibilities far beyond their age.

But what does it actually mean to grow up in the midst of war?

1.0 Bosnia's independence and the outbreak of war

To understand the suffering of children in the Bosnian War, one must begin with the world that collapsed around them.

When the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia disintegrated in the early 1990s, it was not just borders that dissolved, but identities, communities and basic certainties.

In 1992, the Sarajevo-based government, dominated by Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) and Bosnian Croats, declared the independence of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. But this move was met with fierce resistance. The Serbian Democratic Party (SDS) called on Bosnian Serbs to boycott the referendum. On 2 March 1992, just a day after the vote, pro-Serbian paramilitary groups erected barricades in Sarajevo. Fear and tension spread quickly; neighbourhoods turned into fault lines.

Meanwhile, units of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), still under Belgrade's command, refused to leave. Their mission was no longer preserving a federation, but creating a new state project, a ‘Greater Serbia’. Yugoslav and Bosnian Serb leaders made clear they were ready to pursue this vision by force.

By early April 1992, even before Bosnia and Herzegovina’s independence was internationally recognised by the European Community (6 April) and the United States (7 April), the situation had already descended into violence. In the northeastern town of Bijeljina, the first expulsions and war crimes against non-Serbs marked the brutal beginning of the Bosnian War. For many historians, it was the first open wound in what would become a years-long humanitarian catastrophe.

1.1 The Siege of Sarajevo

“We will not tire of telling the truth, because there is no alternative to truth and justice.”

-Senida Karović, President of the Union of Civilian War Victims of the Canton of Sarajevo

To this day, the residents of Sarajevo are still fighting for justice for what happened over 30 years ago. The siege of the city began on 5 April 1992 and did not end until 29 February 1996. For almost four years (1,425 days), Sarajevo was under constant fire. The siege was the longest of any European capital since the Second World War.

Sarajevo lies in a valley surrounded by mountains. Serbian forces set up artillery and sniper positions on these mountains. They also set up barricades and checkpoints that cut off the city from the outside world and made any movement within Sarajevo extremely difficult.

For years, the city was under fire from the surrounding hills. Electricity, heating, water and food supplies were cut off, and many elderly people died in their homes, especially during the cold winter months. There was no safe place for the civilian population: not at home, not at school, not in a hospital. It was no coincidence that these buildings were hit: they were deliberately targeted because they are central locations in everyday life, especially for children and young people.

Investigations are currently underway against so-called ‘sniper tourists’. These are believed to be foreign men who came to Sarajevo during the war to shoot civilians for money. Media outlets such as the BBC and DW have reported on the case and on investigations by prosecutors. Some reports also refer to alleged price lists for specific victim groups, which are still being examined.

The majority who were unable to flee spent their daily lives at home, some of them in basements. Children grew up indoors or underground and did not know what it was like to play outside carefree. Every second they spent outdoors was life-threatening. They crossed streets, crouched down and ran, always at risk of being hit by snipers.

Nevertheless, teachers tried to maintain education. Lessons took place at different times, depending on shelling and danger. Raising a child during a war or growing up as a child in one is unimaginable. Limited food, hardly any fresh air or sunlight, constant stress and fear. Many children were separated from their families, became homeless, traumatised or emerged from the war as orphans. Those who survived and grew up still carry the burden of their experiences to this day.

Adnan Rahimić, who was just 10 years old during the war, describes his childhood in an interview with the Süddeutsche Zeitung:

"Sometimes I wonder what my childhood would have been like without the experience of war. Even though I didn't understand what was happening at the time, the war became part of my life. A permanent, unconscious feeling of threat is deeply rooted in me. I wonder what it feels like to be afraid of a school test rather than fearing death. Not having to hide in a bunker, but being able to travel abroad. The war taught me to take my life more seriously, to appreciate its value and to be grateful to be alive.”

Sarajevo is a city where the war is still visible today: Sarajevo Roses on the streets, bullet holes in the facades, and anti-war graffiti in public places.

In total, over 10,000 people died, including around 1,601 children. To this day, relatives of the murdered children express their anger that many of those directly responsible were never convicted.

Sarajevo is just one of many cities in Bosnia that bear their own history of violence and loss, far more than I could recount in a single article. In the next chapter, I will therefore write about the place that probably made me question humanity the most: Srebrenica.

1.2 Srebrenica Genocide

Just imagine what it's like when suddenly everything seems hopeless. You don't know where to go, you're completely confused, and just trying to survive. You hear different things from all sides: you should go here, it's safer there, or maybe you should go there instead. The UN protection zone seems the most logical option, after all, it is the UN, the United Nations, whose soldiers were sent specifically to protect the population.

But in Srebrenica, everything turned out differently from what people had expected.

Young, old, man or woman, it made no difference. The children of Srebrenica report:

Edita Klančević, then 10 years old, who was able to flee to Germany with her brother and mother and lost her father:

“Even to this day, I cannot find the words to describe what was going through my head at those moments. I was growing up too fast and struggling to grasp the reasons behind the actions of those men and the trip itself. The atmosphere on the bus was dull after that checkpoint. Everyone was occupied in their own thoughts, searching for answers, praying and reflecting on what just happened. I might have been very young at that time, but I realised that my life as I knew it ceased to exist.”

“The 11th of July doesn’t only mark the massacre committed upon innocent and weak, it also marks the attack on the human society itself. Instead of succumbing to despair and sadness, the survivors of Srebrenica insist that the legacy of this crime is addressed. The simple fact is that by allowing the events of July 11 1995, to disappear into the history books, would be a far greater crime than the crime itself.”

Visiting the Srebrenica Memorial Centre and seeing this place with my own eyes was a deeply emotional experience for me. It is not just a museum, but the place where, after the capture of the UN protection zone on 11 July 1995, the genocide of more than 8,000 Bosniak boys and men began, while women, girls and children were displaced and abused. The number of identified victims is still rising as new mass graves continue to be discovered, and people are buried.

So much suffering in one place. So many stories, so many personalities, people with dreams and plans who took their last breath here. All that remains of many are their personal belongings, while others remain buried somewhere underground.

There are also photos and videos: parents holding their children by the hand or carrying them, overloaded with bags and bundles they hastily gathered before setting off in the summer heat. Despair is written all over their faces. Normally, parents try to hide their fear from their children, to encourage them, to give them hope, but here, none of that was possible anymore. There was no way out, no rescue, no plan B. Every moment could be their last. That is probably only a small fraction of the thoughts that went through their minds at the time.

How often do you see your own parents cry? Probably only in very serious situations. I had to think about how heartbreaking this sight must be for a child. The children in the recordings seem confused and exhausted, without understanding what is happening, and above all, innocent.

2. Inside the War Childhood Museum

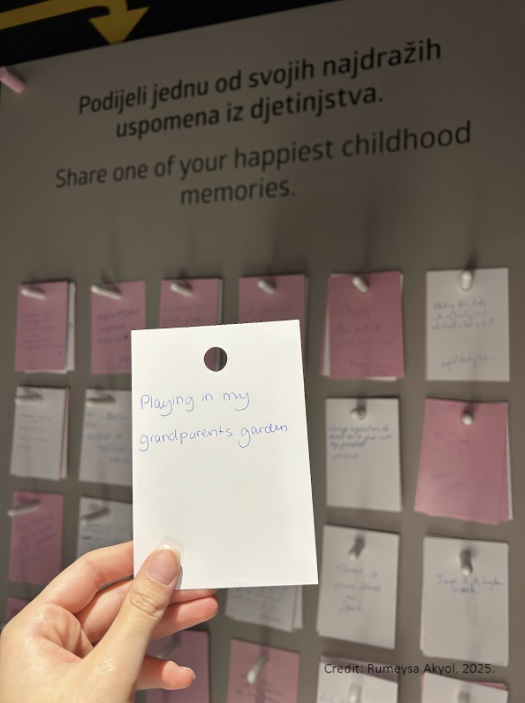

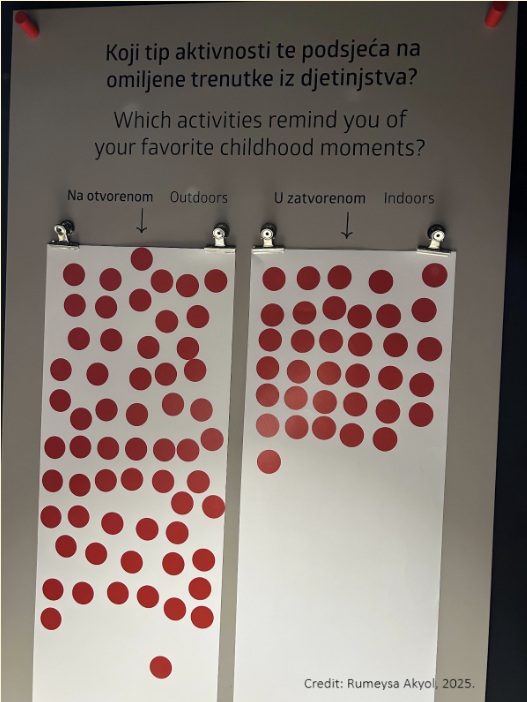

The museum begins with an introductory room that reminded me of my own happy childhood memories through sounds, smells and short questions, and then, in the next room, confronted me with the harsh reality of many other children’s lives.

In this introductory room, visitors can engage with questions, scents and audio stations. We quickly became very excited and realised how much we had in common: what we remember from our childhood, what we used to play and which things were important to us. We answered the questions on the wall with stickers and were able to compare our experiences with one another.

I remember very clearly how our mood suddenly shifted, and we became quiet and focused as we left the introductory room. In the following rooms, we saw countless objects belonging to children from Bosnia, Ukraine and Gaza, each with its own background story. There are so many that the museum cannot display them all at once and has to rotate them regularly. They are not just objects, but mementoes that a child hid and held onto during a difficult time. Years later, these personal items end up in a museum and still carry all of those intimate memories with them.

It all started with a single question that Jasminko Halilovic asked on an online platform: ‘What was war childhood for you?’ Over the course of several days, thousands of people responded, not only from Bosnia but from all over the world.

Two and a half years later, he published his book War Childhood. In this book, he collects sad, painful, and some happy memories of children about their childhood during the war. The book has been translated into several languages and has gained international attention.

Nevertheless, he quickly realised that this was not enough for him. He made it his mission to open a museum in the name of the children who grew up during the war. He stayed in touch with some of the people who had responded to his question. They sent him photos of their mementos, which meant so much to them. Jasminko realised that these personal treasures could be lost over time.

This is how the War Childhood Museum came into being. It has since won several awards and is the first museum dedicated specifically to children who have experienced war.

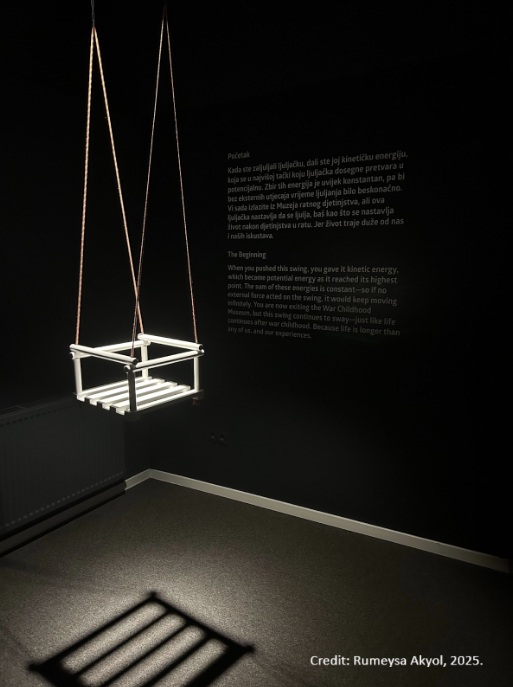

At the end of the exhibition, in a dark room, there is a single swing illuminated from above. It is based on the story of a girl from besieged Sarajevo, for whom the swing in the damp basement was the safest place. A hiding place, a memory of her grandfather and a small piece of childhood left in the middle of war. On the wall behind the swing is written:

The Beginning

When you pushed this swing, you gave it kinetic energy, which became potential energy as it reached its highest point. The sum of these energies is constant – so if no external force acted on the swing, it would keep moving infinitely. You are now exiting the War Childhood Museum, but this swing continues to sway - just like life continues after war childhood. Because life is longer than any of us, and our experiences.

This beautiful closing reminds visitors that life goes on despite all the terrible events and that, with time, new, beautiful memories can be added, even if the traumatic experiences remain.

3. The forgotten children of Bosnia

Before this trip, I knew about the siege and the genocide. But I was unprepared for the stories that are rarely told, even in Bosnia itself. During my research, I encountered the fate of those who live in the shadows: children born of wartime rape.

Learning that sexual violence was not random, but classified by international courts as a deliberate strategy of war, was harrowing. Tens of thousands of women were targeted, and from this violence, a new generation was born. These children carry a heavy history they did not choose, one that was often kept from them.

For years, silence reigned. Mothers remained silent out of unbearable pain, shame, or fear of community rejection. Consequently, many of these children grew up in homes filled with secrets, sensing a lack of belonging, only to face shattering questions about their identity later in life. Today, organisations like Forgotten Children of War are finally fighting to give them a voice and rights that have long been denied.

But the shadows hide other stories, too. I learned about minors who were swept into armed units: child soldiers. Some felt a crushing duty to protect their families, and others simply saw no alternative for survival. They were forced to grow up in an instant. Yet, after the guns fell silent, they received little support or recognition. Many still carry the invisible, psychological scars of their experiences to this day.

Initiatives in Bosnia and Herzegovina are now attempting to break this silence, bringing to light what has been hidden for too long.

4. Reflection: What this journey taught me

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Democracy International and the project organisers Josi, Lia, Ajna, Anne, Teresa, Shirley, Beka and Pierpaolo, who made this educational trip possible. You not only organised a programme, but also created a space where we could learn, feel, listen and grow together.

I can hardly imagine how I could have learned more about Bosnia and Herzegovina than in this diverse group of people who share similar values to me: the desire for justice, an interest in history and politics, and a willingness to engage with difficult issues. In our conversations, whether in the National Library, on the bus, just before bedtime or while eating together, I realised how much power there is in sharing experiences and asking questions together that sometimes have no easy answers.

I am incredibly grateful that I was able to take this unforgettable trip and return with a proverbial suitcase full of knowledge, emotions and memories. Thanks to the workshops, group work, interviews, excursions and conversations, I have expanded my horizons both professionally and personally.

Bosnia's history has always been close to my heart, but this trip and the follow-up research have made me realise once again how much I still didn't know. Learning about the Bosnian War is not an easy thing. It is emotionally difficult, painful and sometimes overwhelming. There were many moments when I had to pause for a moment. I chose this topic for my blog post because, as I said at the beginning, children do not start wars, but they pay the highest price for them. Every child should be able to grow up in a safe, healthy environment and, above all, be a child.

At the same time, this experience has shown me how important it is for us as young people to engage with this history. We cannot undo the suffering, but we can look, listen and learn. The least we can do is exactly that: learn about the Bosnian War, pass on the stories and ensure that history and the victims who fell are never forgotten. For me, this journey is not simply ‘over’, it continues to accompany me, in my thoughts, in my conversations and in the responsibility I take away from it.

Understanding the past is the key to shaping a better future.