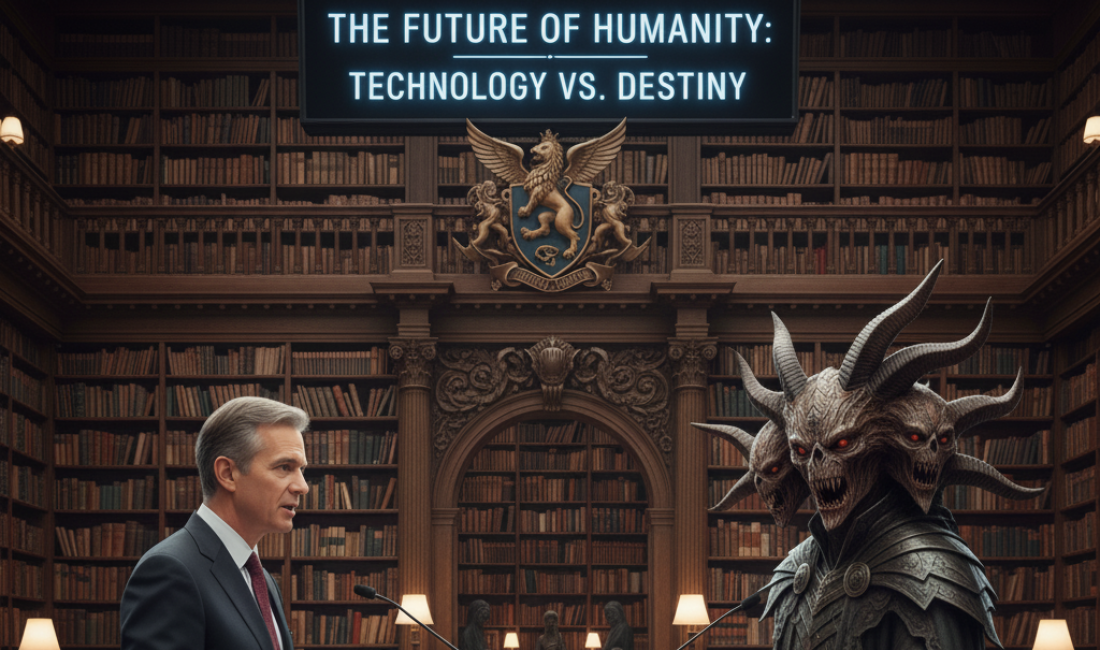

The tech billionaire is talking about the Antichrist. Now the Antichrist talks back

This column is co-published with Zócalo Public Square.

By THE ANTICHRIST, as told to JOE MATHEWS

I admit I can be pretty scary. But I’m nowhere near as frightening as Peter Thiel.

Which may be why the dark lord of Silicon Valley has been targeting me, on podcasts and in a series of four off-the-record lectures in San Francisco.

I can’t read Thiel’s mind—since I’m not from Northern California, I don’t pretend to know everything. But I can’t help wondering if Thiel is giving lectures about me in a desperate attempt to convince humanity that this planet has at least one being more evil than Thiel himself.

My first instinct was not to take Thiel’s bait. I’ve remained silent for millennia as people all over the world project upon me their deepest fears and darkest impulses.

But when I read the leaked transcripts of Thiel’s San Francisco talks in the Guardian (the Washington Post got the leaks, too, but I won’t subscribe to a publication owned by my longtime competitor), I decided to borrow this column from its usual author. (Also, the Commonwealth Club, which hosted Thiel, never gave me the opportunity to respond.)

Peter Thiel accusing me of trying to end the world is—not to bring my nemesis Jesus into this—too much of a cross to bear.

Yes, I may be, as the Book of Revelation suggests, a Satan-empowered beast with 10 horns and seven heads. I may rise from the sea, take over the world, charismatically criticize God and Christ, persecute believers, and inspire people to tattoo “666” on themselves.

But at least I’m no tech bro.

I’ve never been as ambitious, or as dangerous, as Thiel and his Silicon Valley ilk. They seek to dominate the world technologically, economically and politically, even if it means upending the lives of billions, extending mass surveillance, or threatening democracy.

In contrast, I’ve long existed to warn humans of their power to destroy themselves and the world. Indeed, there was an Antichrist before there was a Christ. I first showed up in the Old Testament, in the Book of Daniel, which predicted that a king would rise to “speak great words against the most High” and persecute people to their death. Scholars say the idea of me was inspired by the ruler Antiochus IV, who attempted to wipe out Judaism two centuries before Jesus’ birth.

I’ve endured because I’m so terrible that I’m useful in casting aspersions, primarily on powerful political and religious leaders and institutions, from the Roman emperor Nero to Napoleon, Hitler, the European Union, and baseball pitcher Roger Clemens, all of whom have been accused of being me.

I’ve also inspired philosophy and centuries of art, including Lars Von Trier’s 2009 film Antichrist, which is a tough watch even for me, since it starts with a baby’s death and ends in sadomasochism.

But while I’m a bad guy, I’m not in Thiel’s class of badness.

For example, the 13th chapter of Revelation has me ruling the world for 42 months, less than one presidential term. Thiel, who helped Donald Trump win two terms, has already spent decades disrupting lives and democracy at the top of tech.

I’m also not a hypocrite—unlike Thiel. He’s an immigrant who funds anti-immigrant nationalist politicians, and a graduate of San Mateo High and Stanford who rails against public education and discourages people from going to college. A man who grew wealthy from being able to start businesses in your free and democratic country now opposes women voting and maintains that freedom is incompatible with democracy.

And while I have no record of craziness or fabulism, Thiel is a nutty conspiracy theorist, as you can tell by reading his speeches about me. He rants about Caesar-Papist fusion (in which the U.S. president and Pope would rule the world together) and one-world government. He approvingly quotes the Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt as a guiding light.

Thiel seems to see me not in the world’s most evil leaders, but in younger, less powerful people trying to do good. He suggested that the Swedish climate change activist Greta Thunberg might be me. And he argued that the world will be ended by an “Antichrist-type figure who cultivates a fear of existential threats such as climate change, AI, and nuclear war to amass inordinate power” to stop technology and tax the very rich.

Global financial and legal institutions, like the International Criminal Court, are hastening Armageddon, he said, observing that “it’s become quite difficult to hide one’s money.”

In essence, Thiel is using me to paint a target on do-gooders and those who might limit the powers of great and ambitious men like myself. I’m the Antichrist, so I can take that kind of heat. But he is endangering young people in civil society who are working for a better world. This strategy is not a new one—racists and antisemites around the world have long accused those who oppose them as the Antichrist. In South Africa, the Afrikaner Resistance Movement was obsessed with the Antichrist.

But nowhere has the search for the Antichrist, and for the people or institutions who might be serving me, been more intense than in the United States. In his religious history, Naming the Antichrist, theologian Robert C. Fuller argues that Americans, by viewing our nation as divinely inspired, are especially devoted to demonizing our enemies.

Thiel’s attacks on me are part of an American tradition. And his targeting of me proves my enduring value. When people speak of the Antichrist, they reveal their own prejudices and intentions. It’s not unlike, say, a president who, in lawless pursuit of crime, reveals his own criminal aims.

The harder truth about the Antichrist is just how easy it is to locate me just about anywhere. The world’s greatest horrors can’t be perpetrated by a few leaders or one reckless inventor. Great crimes require the cooperation of millions of everyday people.

So, Peter Thiel, you can stop your search for the Antichrist.

You can find me just by looking in the mirror.