The Case of an Unarmed Hippie Takes on New Relevance

This column is co-published with Zócalo Public Square.

Might the answer to Southern California’s present emergency—how to stop masked federal agents from seizing its people—lie in a half-century-old story from the North State cannabis lands of Humboldt County?

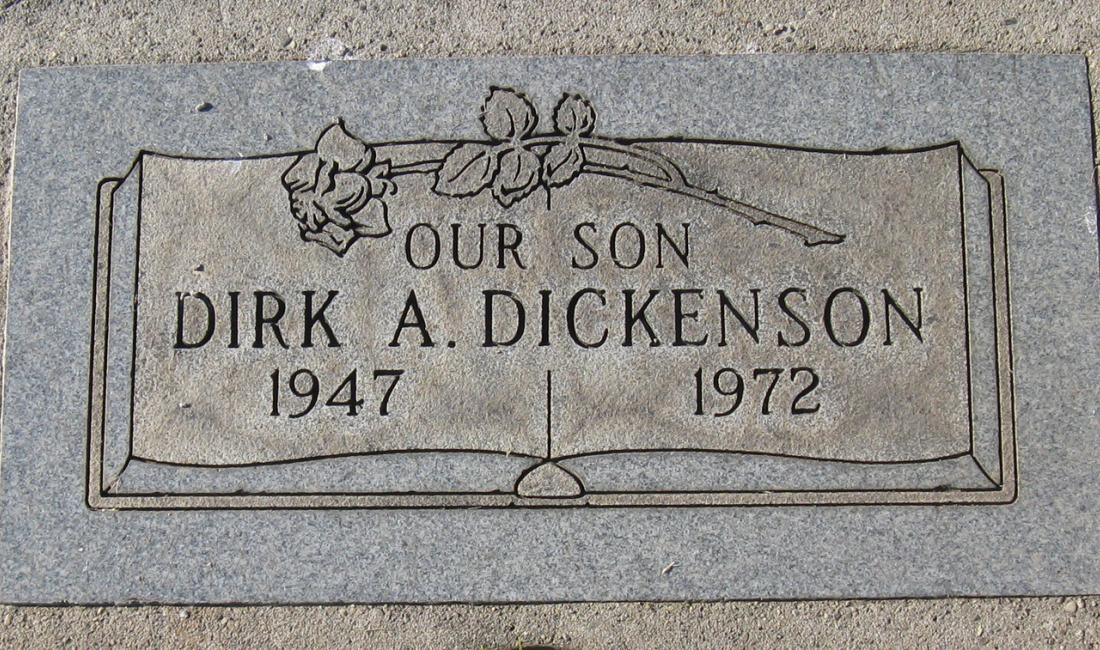

On April 4, 1972, a hippie couple—24-year-old Dirk Dickenson and his girlfriend Judy Arnold, who had relocated from the Bay Area—were drinking Jack Daniel’s in their remote cabin outside the tiny unincorporated town of Garberville when a U.S. Army helicopter landed on their property.

Meanwhile, 19 people —including federal drug agents, county sheriff’s personnel, and the local dogcatcher—advanced by car, and then foot, on the cabin. The sheriff had invited three reporters along to see what he touted as the “biggest bust” in California history.

“Looks like an assault on an enemy prison camp in Vietnam,” one reporter wrote in his notebook.

Lloyd Clifton, an agent with the federal Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (now the DEA), led the way inside. He and other agents wore jeans and tie-dyed shirts instead of uniforms, and kept their hair long. Arnold testified that she and Dickenson thought they were being robbed when Clifton and company broke down the cabin door without knocking or announcing themselves as law enforcement.

Dickenson, who was unarmed, ran out the back porch and down the hill. Clifton pulled his .38 revolver and gave chase. He later claimed he thought a colleague had been shot (that agent later testified he had tripped). Clifton ordered Dickenson to halt, and when he kept running (perhaps because he couldn’t hear him over the helicopter noise), shot him in the back. Dickenson bled to death while being transported to a Eureka hospital.

What happened next gives this killing lasting relevance.

The agents couldn’t find the PCP lab that an informant had claimed was on the property. Indeed, no large drug enterprise could have been run from a cabin without electricity or water, and the agents found only a small stash of recreational drugs for personal use.

Nevertheless, the U.S. Department of Justice—later revealed during Watergate to be a deeply corrupt branch of the Nixon administration—defended the federal agent, quickly declaring Dickenson’s execution a “justifiable homicide.”

But Humboldt County District Attorney William Ferroggiaro refused to go along with the DOJ. Ferroggiaro argued, correctly, that federal agents are subject to state and local laws. The prosecutor took the case to a grand jury, which charged Clifton with second-degree murder and voluntary manslaughter.

Clifton’s indictment became a national news story and sparked a debate about the impunity of federal agents. And the ensuing court fight established a clear, if difficult, legal path for investigating and holding accountable the lawless federal secret police now swarming our streets.

The existence of any path at all may come as a surprise to today’s Californians. That’s because our local officials, especially police leaders, keep telling us that they are powerless to challenge unlawful actions or abuses by ICE and other federal agents.

California may be a legal “sanctuary” for undocumented immigrants, but police leaders maintain that means only that they do not cooperate with federal enforcement actions. Actually protecting immigrants—and even U.S. citizens—from ICE and Border Patrol would amount to interference with the feds. Pressed on this subject recently, Los Angeles Police Chief Jim McDonnell advised his officers that, when called to a scene of federal action, all they can do is verify the identities of federal agents.

In this, McDonnell and police leaders are not just wrong—they are transgressing their oaths to enforce state and local laws, and to investigate violations of those laws. Revisiting Clifton’s killing of Dickenson makes this plain.

In 1973, Clifton first sought to convince state courts to drop the prosecution, but he failed. With the trial about to start, Clifton appealed to the federal courts, arguing that as a federal agent, he was beyond the reach of state law.

The federal courts did not accept Clifton’s argument. But in 1977, Clifton succeeded in convincing the U.S. Ninth Circuit to let him free, on the theory that he “reasonably and honestly” believed Dickenson was a dangerous drug dealer, even though Dickenson wasn’t. In his Clifton v. Cox ruling, U.S. Judge Stanley Conti wrote that federal law enforcement officials could be prosecuted for state and local crimes when:

“the official employs means which he cannot honestly consider reasonable in discharging his duties or otherwise acts out of malice or with some criminal intent.”

Establishing malice and criminal intent is a high bar, but lawyers and others eager to pursue ICE personnel in California are now revisiting the Clifton standard. So are members of the public. In a June YouGov poll, commissioned by the Independent California Institute, 72% of Californians said that police should arrest federal immigration officials who “act maliciously or knowingly exceed their authority under federal law.”

Recent federal abuses, captured on video, would seem to meet the Clifton test for prosecution. A federal agent’s repeated punching of a Santa Ana landscaper, slamming the man’s head against the pavement. A retaliatory attack by federal agents, using explosives, on the Huntington Park home of U.S. citizen protesters.

At the very least, the Clifton case, by making clear that federal agents are not above state and local laws, should open the door for local police in California to document and investigate every single one of these lawless ICE raids. Given the scale of the federal assault on immigrant communities, I’d suggest that police departments create a joint task force, perhaps in collaboration with a new state authority countering the federal threat.

Some may object that the contexts of 2025 Los Angeles and 1970s Humboldt are too different. But I was struck while rereading records of the Clifton litigation, as well as a 1973 Rolling Stone story by Joe Eszterhas, by how strongly Nixon-era federal abuses parallel today’s Trump moment.

Indeed, the Clifton raid was part of a flurry of federal drug raids. Federal agents frequently violated suspects’ rights and seized people on little evidence. That is how they ended up targeting Dickenson, who made wood tables for a living, as a drug dealer. It’s the same brand of recklessness and incompetence that ICE and Border Patrol demonstrate today in rounding up U.S. citizens and law-abiding residents while doing “immigration enforcement.”

In the 1972 case and in this summer’s raids, federal agents do not identify themselves, receive military assistance (like that helicopter), and dress in ways that make people think they might be criminals. Then as now, the federal government also loudly touts its attacks against supposed “invaders”—back then, urban hippie migrants who had relocated to the North State and clashed with more conservative locals.

And the Nixon administration, just like the Trump administration, justified lawlessness by claiming that federal agents were the real victims in these cases.

“All of our institutions in this country are under fire today,” a federal attorney representing Clifton wrote at the time, “and…. the police perhaps more than any other are called in question by radical elements in our society, who for reasons of their own desire to bring our country down.”

California’s 1970s-era drug war and the U.S. government’s present-day immigration sweeps both have violated civil rights, hurt communities, and corrupted law enforcement.

After the federal judges canceled his indictment, Clifton continued his career. His 2013 obituary briefly mentioned his DEA service, instead dwelling on his devotion to his family and to Hayward, the same East Bay city from which Dickenson and Arnold had moved to that cabin outside Garberville.

Dickenson was buried in Lincoln, in suburban Sacramento, near where he grew up. Tragically, he and his loved ones never received justice. But his precedent-setting case remains very much alive.