Learning journalistic and democratic skepticism through my mother-editor.

I first tried journalism when I was 6. My family was living in Beijing, and I handwrote a two-page newsletter for children and adults in the U.S. expat community.

After I made a mistake, a veteran American journalist, then the Beijing bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times, took me aside and explained how important it was to double-check everything—especially those things of which you feel most certain.

The journalist conveyed this to me with an old reporting adage:

“If your mother says she loves you, check it out.”

I’ve never forgotten the adage. Not least because the journalist who shared it was my very own mother.

My mother taught me a lot about journalism. She still teaches me, though more quietly than before. You certainly wouldn’t be reading this column if not for her. But, with Mother’s Day approaching, and our family’s profession and country mired in crisis, Mom’s lessons about love seem urgent.

Her biggest lesson might be that true love is conveyed not just through hugs and trust. Love is hard, because all the people and things we love are untrustworthy in some ways. Love requires hard skepticism and relentless questioning—two habits she generously gifted me.

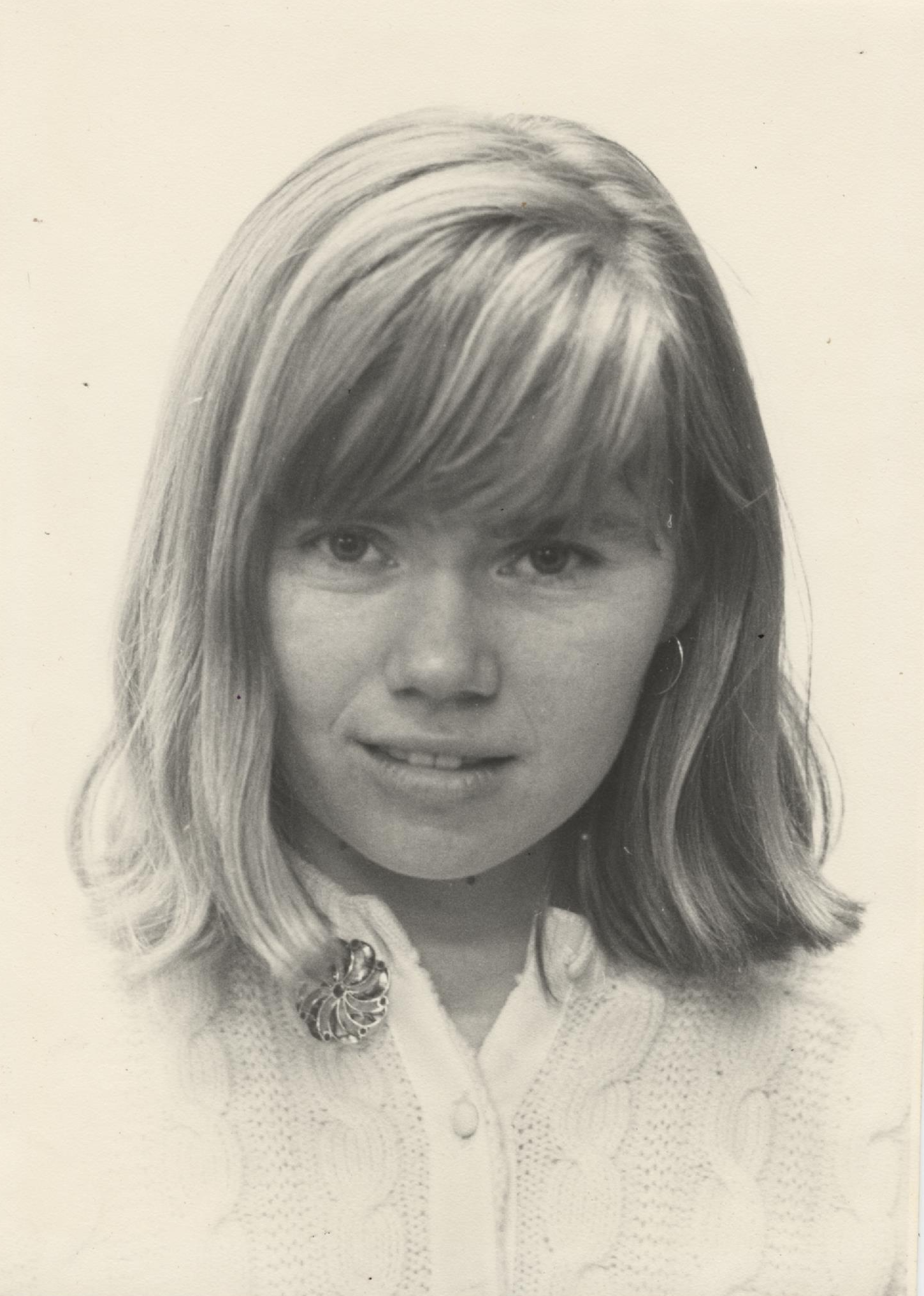

Linda (nee McVeigh) Mathews was born in the Inland Empire town of Redlands, where her grandparents and parents had migrated during the Dust Bowl. But she grew up mostly in Hawthorne, near LAX. She attended public schools, and was a classmate of the Beach Boy Dennis Wilson at Hawthorne High.

She loved to tell stories of early 1960s Southern California. Her favorites were about long car trips on Imperial Highway (before the freeways) to see relatives in Redlands, and about her high school class, post-prom, walking out onto the empty 405 freeway, which had been constructed but not yet opened to traffic.

Neither of her parents had gone beyond high school. Her mother was an assembly line worker at North American Aviation, which later became Rockwell; her father did custodial work and delivered newspapers. Mom was always honest about her parents’ difficult marriage, which her father’s alcoholism cut short. But she always encouraged me to call and seek out my grandfather.

Mom, through great intelligence and perseverance, won a scholarship to Harvard. She got the journalism bug at the Harvard Crimson, the campus newspaper, where she met my father, who would spend his career at the Washington Post.

She also learned how to ascend in a world full of glass ceilings. In her junior year, she was named the paper’s managing editor, the first woman to hold the role. Her appointment made national news when the Yale Daily News managing editor John Rothchild, later a successful finance writer, sent her a note that read:

“OK you did it. As a member of the female conspiracy to undermine maleness, you have successfully broken into another heretofore male institution,” he wrote, concluding with a challenge to her “at your weakest point, the area so much neglected by modern women: femininity” by proposing they play the “girl’s game” of jacks.

She lost at jacks, but won a spot as a contestant on the TV game show “To Tell the Truth,” and admission to Harvard Law. It turned out that she didn’t like the law—and how rules reflect the preferences of those in power, not what’s right—and switched to journalism.

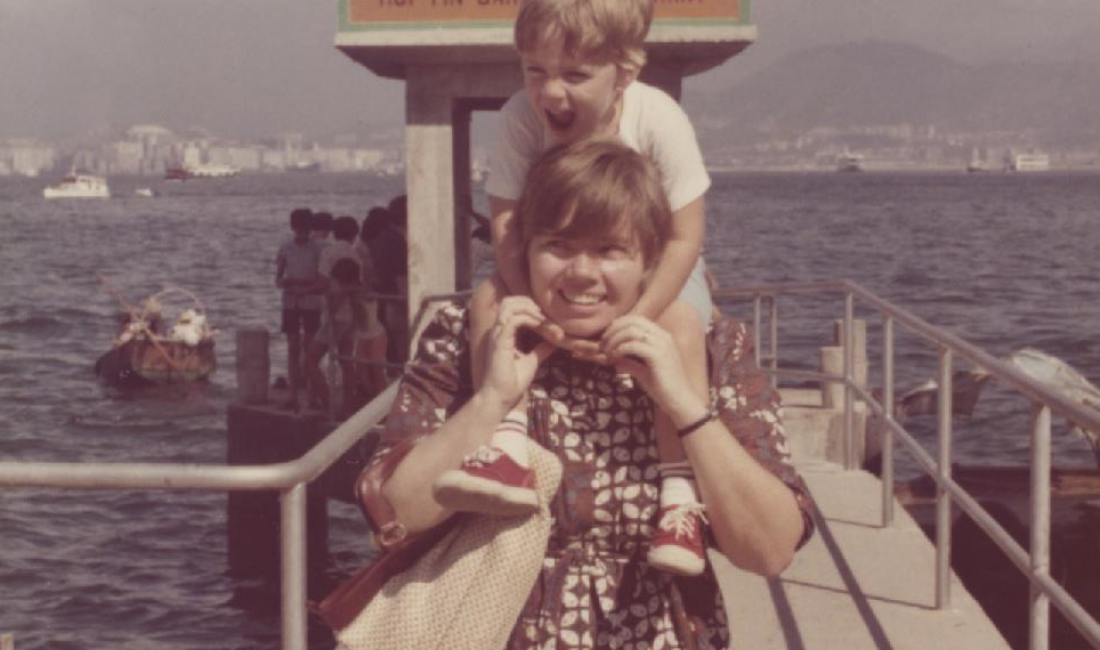

I was a close witness to her career, and watching her bump up against obstacles taught me never to trust newsrooms, or the people who lead them. She only got hired by the L.A. Times when the top editor, who didn’t want “girls” on the paper, was on vacation. When my father got transferred by the Washington Post to Hong Kong, the L.A. Times refused to send her to compete against my dad. After a year of her out-scooping him at the Asian Wall Street Journal, the Times hired her back.

When she returned to L.A., she sought to rise in the editing ranks, but always seemed to end up deputy to a less diligent man. She eventually left for ABC News, the New York Times, and USA Today, where she had prominent jobs, but never the top one.

I’ve talked to her colleagues, many of whom became my colleagues when I was a reporter, and they told me a similar story. She was a victim both of glass ceilings and rough style. Reporters and editor colleagues loved my mom, and her unvarnished directness, her utter lack of vanity. The L.A. Times columnist Sandy Banks recalls Mom working on a frantic foreign desk, not minding that breast milk was leaking through her blouse (she had recently given birth to my baby sister). Sandy pointed it out. Mom said it could wait until after deadline.

Her smoother bosses appreciated her skill and hard work but some found her too unsparing of people’s feelings. She believed strongly that honesty, even unpleasant honesty, is a requirement for journalism. We have to tell each other the truth if we are going to give readers the truth. But her direct style, that of the working-class Hawthorne girl, cost her.

I confess that her experiences deeply influenced my own choices. In personality and style, I’m very much my mother’s child. Which is why I’ve always remained a reporter and rejected offers to become an editor or chart a path to being a newsroom leader. If someone as brilliant and honest as my mom was blocked by journalism politics, what chance would I have?

I’m grateful I made that choice, as the journalism business grows ever more political and prissy, and less interested in hard truths.

I benefited from following Mom’s path in other ways. I ended up going to Harvard, where I also became managing editor of the Crimson and married one of my fellow editors, who also grew up to be a career journalist. Mom married young (she was 21) and I married young (23). Both our unions have held.

I became the sort of journalist she was, skeptical about everything, always asking questions, and direct with bosses. Career opportunities took me east for a few years, but I returned to California, just as she had. She loved the place, despite the fires and earthquakes, because it was warm and you could be yourself. In our long and complicated family history, California was the only place where our Scots-Irish clan had found any sort of prosperity.

My mom never left behind her large extended family, still a working-class clan of truck drivers, school bus drivers, along with a few teachers and reporters. And she encouraged me to write about all the dusty, mostly ignored places where our relatives lived, from Apple Valley to Modesto. I’ve done that, often sleeping on family couches and guest beds in the process.

That’s allowed me to see communities with loving, local eyes. Until recently, my mom would give me feedback on stories; she could be a tough critic, particularly of wordiness and sentimentalism. I always worked harder on stories knowing that she would read them.

Now she has Alzheimer’s. With my dad’s great assistance, she remains active, still showing up for family events and for my children’s baseball games.

She copes with the disease in a familiar way, by constantly asking us skeptical questions. With every query, I feel her love.