6,500 Miles Away From Home, a Possible Tsunami Taught Local Lessons

This column is co-published with Zócalo Public Square.

All global emergencies are local.

Sometimes, as I recently learned, doubly so.

The South Pasadena Pride, a 14-and-under youth baseball team, had taken the lead with a four-run rally in the second inning, and, with no outs and two men on, was threatening to blow open the game when my son stepped up to the plate.

Then a siren rang out—too loud to ignore.

Our players, our parents, our coach, and I (the team organizer-manager) were unsure what it meant and what exactly we were supposed to do.

We didn’t want to stop the baseball. We had traveled 6,500 miles from Southern California to the small town of Kunigami, on the west coast of Okinawa, to play against local teams on the Japanese island. The trip was spurred by two of our former players, whose families had moved back to Japan (one to Tokyo, the other to Okinawa) in recent years.

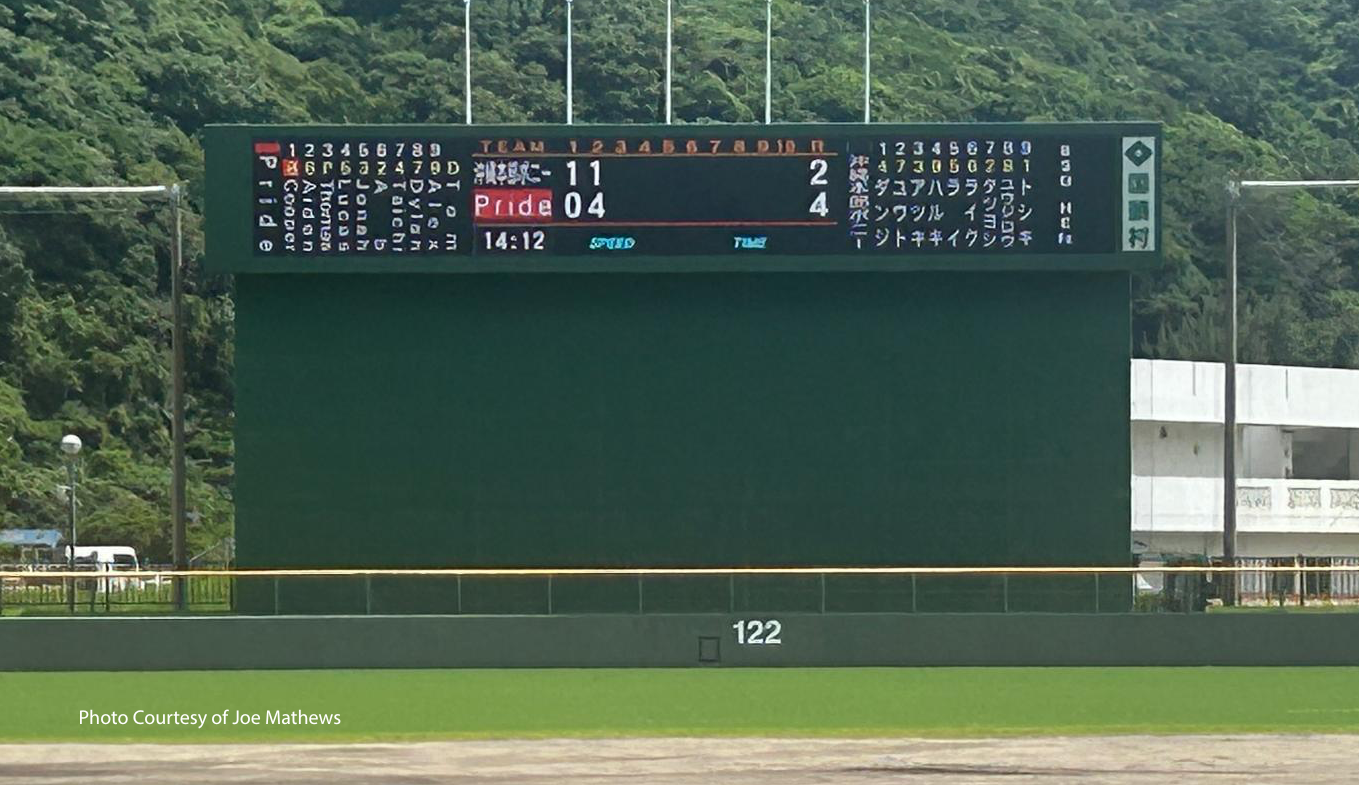

Much to our team’s delight, that day we were playing at Kaigin Stadium, which is the spring training home of the Nippon Ham-Fighters, the Japanese major league team for which Dodgers star Shohei Ohtani played. This was our first of three games scheduled for the afternoon. It would be our last time ever playing with our Okinawa-based teammate, a pitcher, who was scheduled to take the mound later in the game.

But with the siren, the umpire stopped play, stalling our momentum. After a few minutes of standing around, we returned to our dugout to escape the oppressive heat and humidity before our Japanese-speaking parents gave us the news:

A tsunami warning had gone out for the entire island of Okinawa, triggered by a massive earthquake in the Western Pacific off the coast of Russia’s far east.

The tsunami warning system went global after the 2004 tsunami that decimated oceanfront communities across the Indian Ocean. The Pacific Tsunami Warning System is its centerpiece.

It’s a combination of two networks. One consists of seismic stations, DART (deep ocean) buoys, and coastal tidal gauges to detect possible tsunamis. The other is a warning and emergency response network that is supposed to reach every Pacific coastal community. For both systems to be successful requires not just skilled local governments, but the participation of people all over the world.

Minutes after the siren stopped our game, loudspeakers in the surrounding neighborhood issued a detailed warning in Japanese. I learned later that they’d been installed as part of Japan’s national J-Alert system, which sends warnings to neighborhoods, schools, and hospitals all across the country.

We huddled with our opponents, from a small coastal town called Motobu, whose phones were also starting to ring with J-Alert tsunami warnings.

Then my phone went off too. But the emergency alert on it was not for Kunigami or Okinawa. As your columnist, I’m signed up for emergency alerts around the state, and Santa Barbara County emergency services was advising me to seek higher ground, away from the coast. A couple minutes later, my home county, Los Angeles, sent a similar warning. The phones of our parents and some players buzzed with the same text.

Of course, had we been playing on our home field back in South Pasadena, we’d be more than 20 miles inland. But home plate at Kaigin Stadium is just 100 yards from the East China Sea.

It wasn’t clear exactly what we should do. The people in surrounding Kunigami neighborhoods, just feet above sea level, were not evacuating. Some poked their heads outside but went back into homes. In their defense, the loudspeaker announcements were scratchy and hard to hear. Two neighbors I spoke with, via translation, said they couldn’t see any way that a tsunami would reach the western side of the island; they might evacuate if they were on the eastern, Pacific side.

We moved to an air-conditioned room in the clubhouse, and admired a picture of Ohtani doing his spring training here in 2014. My son, impatient, asked me to warm him up to pitch, in the pro-style bullpen. But then, after some conversations and texts between parents and local authorities, out of an abundance of caution, both teams decided to move from the dugout to the top of the stands.

There, on our phones, we looked out at the placid, azure sea and read in the New York Times that local warnings were being issued all over the Pacific basin, as far away as Australia and Chile. No one—not stadium personnel, not our opponents—seemed to think that a tsunami would reach Kunigami. Nonetheless, after 45 minutes, island authorities, citing guidance from Japan’s prime minister, ordered an evacuation.

We piled into our rented minivans and followed the Motobu team bus up a small nearby mountain to the Kunigami Forest Park. It was an ecological park, mixing outdoor spaces showcasing plants and trees with indoor exhibits.

The day was sweltering and, about an hour into the evacuation, we got caught in a downpour. Seeking shelter and bathrooms, our parents and players paid $3 to enter an air-conditioned art-and-play building for toddlers and kindergarteners.

I spent the next two hours trying to keep the young ballplayers from pelting each other while they played in a pit of wooden eggs. Shortly after 1:30 p.m., and a takeout lunch of taco rice, the evacuation warning was called off, and we drove back to the stadium to try to resume the game.

We barely finished warming up when the municipality intervened, saying the tsunami threat remained ongoing. Our opponents protested politely, pointing out that the evacuation and warning had been lifted, to no avail. The first game would not be resumed, and our two scheduled afternoon games would not be played. We drove 45 minutes down the coast to our hotel, which kept access to its beach walkway closed for the next 24 hours.

The earthquake, despite its size, did not produce dangerous tsunamis in Japan or anywhere else. But in the aftermath, the Japanese press questioned why people around Japan hadn’t responded to evacuation orders, like those broadcast over Kunigami’s shaky speakers. In an editorial, the Yomiuri Shimbun, a leading Japanese newspaper, said that the millions of summertime visitors to Japan had been left uncertain about what to do, since warnings and evacuation orders were broadcast almost entirely in Japanese.

We were lucky to have an opposing team to guide us. We were lucky to have our two Japanese players, and their parents, present to translate the warnings for us.

We were lucky that the tsunami threat wasn’t closer or more dire.

We were also the benefits of good design. We saw firsthand that the world has a working tsunami system, with global reach and local notice. Warning systems for too many other kinds of emergencies—fires, diseases, wars, terrorist attacks—lack the same reach. Back in January, just five miles from our hometown, a firestorm killed 17 people in Altadena, which did not receive local warnings until it was too late. If only major fires were considered global events, worthy of universal local warnings.

That said, warnings only work if we all follow them. The temptations to ignore warnings are there—part of me preferred to stay and get two more games in that idyllic stadium, with our Okinawan player.

But we followed the evacuation orders, and all our players made it home safely.

Which means, perhaps someday, that we can all return to Kunigami and finish those games.