Invented in Oakland, Fantasy Sports Has Us in Its Grip

This column was co-published with Zócalo Public Square.

Why can’t I quit fantasy football?

I recently asked myself that question during the third hour of a five-hour-long draft that consumed too much of a beautiful summer Saturday. This is my 18th season participating in a nearly-30-year-old fantasy league, run by some old friends in Redondo Beach.

Perhaps my addiction to fantasy football is simply habit. Or perhaps my problem is just that I’m Californian.

The Golden State has a talent for inventing marvelous, irresistible things—from the smartphone to motion pictures, Rocky Road ice cream to the Korean barbecue taco. But sometimes our creations merely waste time and give us headaches.

Consider the Popsicle (they melt all over before you can finish them) or the wave at stadiums (sit down and watch the game, fans!).

Fantasy football is another one of our lesser inventions, handed down to us by journalists—who, as readers of this column know, are full of bad ideas

Their names—may they live in infamy—were Gordon “Scotty” Stirling and George Ross, both of the Oakland Tribune. (Stirling’s name may be familiar—he later had a career as a sports executive with the Raiders and the NBA’s Golden State Warriors and Sacramento Kings.) Stirling and Ross were covering the AFL’s Oakland Raiders in 1962 when they came up with the idea of fantasy football with the team’s part owner, Bill “Wink” Winkenbach, who had already invented fantasy-style games for baseball and golf.

They soon created the first fantasy football league, the Greater Oakland Professional Pigskin Prediction League (GOPPPL)—with other journalists and Raiders officials. These first owners gave a trophy to the winner and a dunce cap to the team owner who finished last. The idea soon spread to the general public through the King’s X, a bar in Oakland whose owner had been part of GOPPPL.

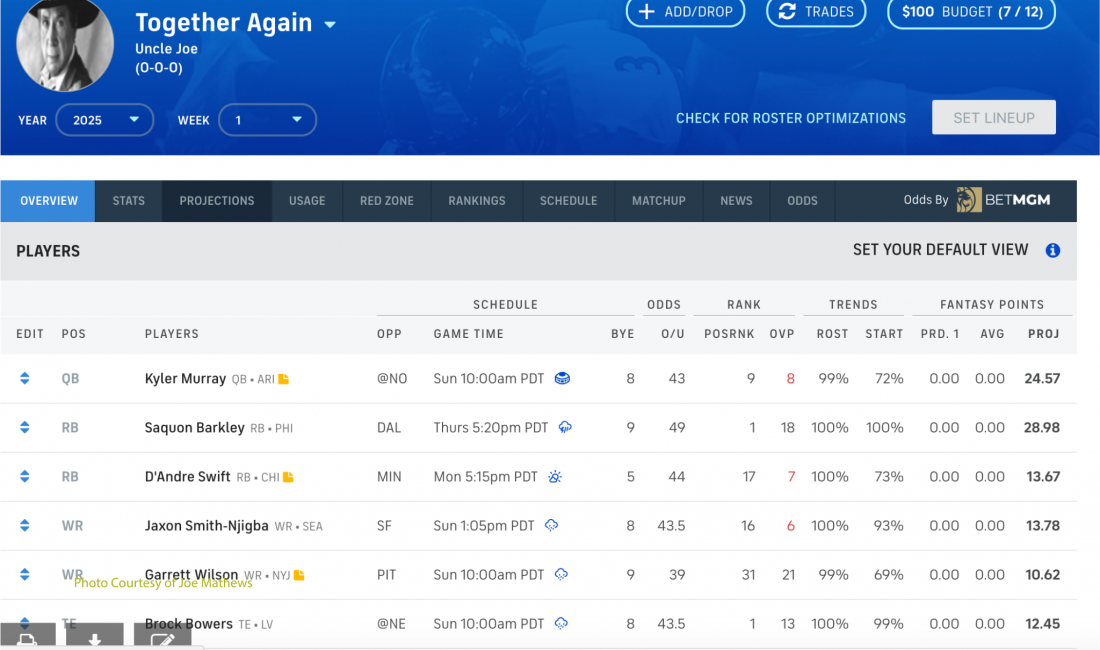

The fantasy football concept endures six decades later. Sports fans like me form leagues with friends, which are hosted online. Then, we “draft” quarterbacks, running backs, wide receivers, kickers, and defenses from different NFL teams to build our own mix-and-match fantasy squads. We compete in weekly head-to-head games in which our teams accumulate points based on the number of yards and touchdowns racked up by the players on our rosters. Toward the end of the NFL season, the fantasy teams with the best records advance to playoffs, which produce a champion.

The journalists Stirling and Ross, showing the lack of business sense typical in our profession, never copyrighted their idea. So they never made money as fantasy sports grew to an industry, with nearly 60 million players in the U.S. and Canada and an estiamted $25 billion in annual revenues today.

For many years, the companies who hosted fantasy sports leagues were media companies that also reported on real-life games, like ESPN or Yahoo. The newest growth in the industry comes from sites like DraftKings and FanDuel, which are online gaming platforms.

Fantasy football has always been gambling. We team owners are betting on the individual performances of the pro players on our teams, and the companies who platform our fantasy leagues are basically bookmakers. But these fast-paced, “daily” fantasy sites, which allow people to place bets every second, have created new addiction risks and are raising legal questions.

On July 3, California Attorney General Rob Bonta issued a formal opinion declaring that fantasy sports sites violate laws against sports gambling in California. The opinion says that any site with participants in the Golden State is operating here illegally. Even if the site itself is based in Boston, like DraftKings, or in New York, like FanDuel.

But, as of this writing, Bonta is letting fantasy sports sites operate in defiance of his legal opinion—despite heavy lobbying from tribal casinos, which have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on ballot measures to stop fantasy gambling. All that money hasn’t convinced Gov. Gavin Newsom, a defender of fantasy sports, to back a shutdown.

I’m not holding my breath waiting for the attorney general to ban my league.

We’re unlikely to be targeted, because we’re an old-fashioned league of weekly games between owners on a site run by CBS. But money is at stake; the annual league fee is $250, and you get a payout if your team finishes in the top three.

The 12-team league started in the 1990s as an extension of a flag-football team on which some of us played. I resisted joining the fantasy league in the early years—I prefer baseball to football. But friends encouraged me to apply (yes, you must write a letter to gain admission). I secured my spot after promising never to win the championship—a promise I kept for 17 years, finishing runner-up four times.

I enjoyed the competition and perfected a draft strategy: stalling. When it was my turn to choose a player, I talked about books and global politics, only submitting my pick when fellow owners started to threaten physical violence. This worked because I’m the only teetotaler in the group; the more they drank, the worse my fellow owners’ picks got.

In those early years, I appreciated the adult male camaraderie (11 of the 12 owners are men), especially while my sons were very young. But after the first decade, there was less banter (the other owners had growing kids, too), and fantasy football began to feel like another boring online chore. You have to check on your team multiple times a week, pick up “free agents” to replace injured or underperforming players late on Wednesday nights, and wake up Sunday morning to choose which people on your team will play.

As work and family responsibilities grew, I turned control of my team over to a friend’s teenage son. When that kid left for college last year, I wanted to quit—but other owners convinced me to play one more year.

I paid little attention to my team, Act Naturally (I always name teams for country songs, this one by the late Buck Owens of Bakersfield)—and was shocked when it slipped into the playoffs and took the championship. I won $1,200 (which I donated to my publication, Democracy Local) and a champion’s jacket. I could retire in peace.

Except I was told it would be poor form to quit after winning, so I agreed to helm one more team, Together Again (also a Buck Owens classic).

Just one more season. After that, I’m giving up on the very bad California idea of fantasy football.

I swear.