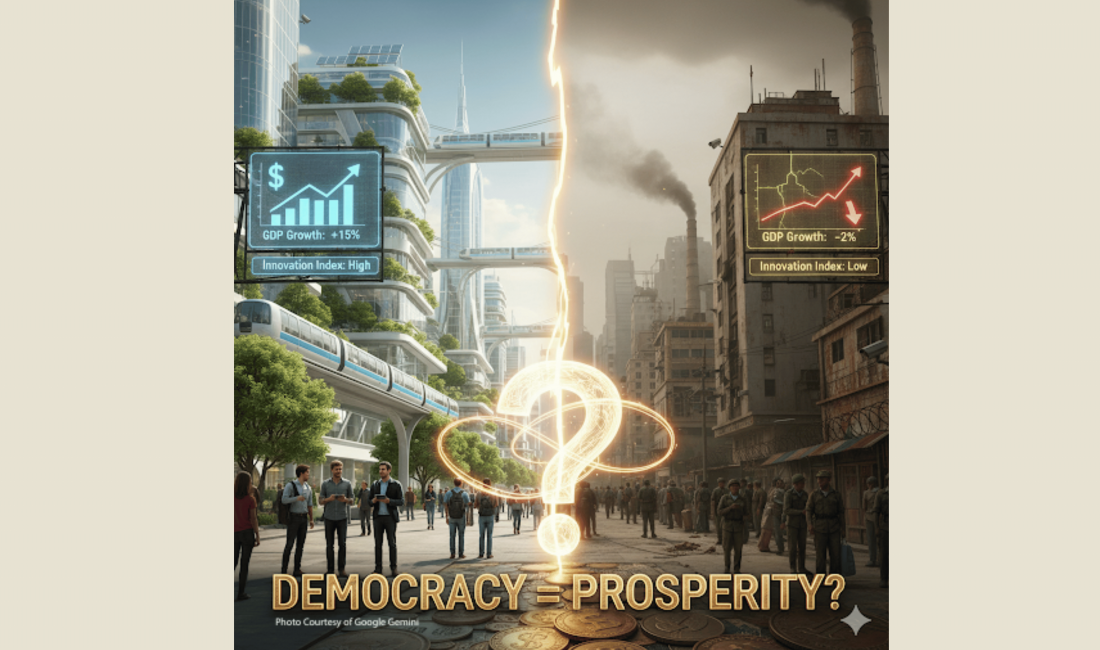

Do Prosperity and Democracy Still Go Together?

This piece was produced and published by SwissInfo.

During a visit to Uzbekistan in June, Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico seemed won over by the economic dynamism of his hosts.

“More and more I wonder if Europe should consider reforming our political system, based on free democratic elections, in order to remain competitive,” Fico said.

For him, places like Uzbekistan, China or Vietnam are simply more decisive.

“When you have a government of four political parties, you can’t compete”.

Can’t you? With a few oil-rich exceptions, the world’s wealthiest countries still tend to be freer (see chart). Switzerland, as a very rich, competitive, and democratic place, even looks like a poster child for the link (the country also happens to be run by a four-party coalition). Yet in recent years, China’s economic rise and the spread of discontent in some Western states have soured the belief in democracy as a sure path to prosperity – and not just for Fico.

An Old Story

Historically, the idea of a connection between democratisation and wealth in the first place was largely a product of the post-Second World War era.

On the one hand, it was part of the global battle for influence, as a cornerstone of the model of capitalist prosperity that the US-led West held up against Soviet communism. But it also became a topic of academic research.

“The more well-to-do a nation, the greater the chances it will sustain democracy,” US political scientist Seymour Martin Lipset famously wrote in 1959, in a foundational statement of what became known as “modernisation theory” – the idea that as societies develop, their politics naturally become more liberal and democratic.

The theory, and the politics behind it, wasn’t without its critics. Lipset himself acknowledged that there are so many factors – education, urbanisation, natural resources – playing into development that it’s too simple to just look at GDP and democracy. Others attacked it for being loaded with assumptions about what the ‘ideal’ society should look like.

Is the end-point of human development inevitably Western, liberal and consumer-capitalist?

And what should come first: economic modernisation or political reform?

Democracy Delivers

Yet despite disagreements, the notion that development and democracy go hand in hand lasted. In 2023, Foreign Affairs magazine labelled it:

“the greatest claim to being a genuine Washington consensus”; the previous year, the US Biden administration had launched Democracy Delivers, a foreign aid project designed to show that democracy doesn’t just bring abstract freedoms, but also material gains.

More recent studies also haven’t signed off on the link completely. But there are often caveats. In 2019, researchers including the 2024 Nobel Economics laureate Daron Acemoglu found that moving from autocracy to democracy boosts GDP by 20% over a 25-year-period. However, their data stops in 2010; the 15 years since then haven’t been kind to democracy globally. The study also doesn’t say why countries switch systems in the first place. Acemoglu has said there is “no mechanism” to suggest that countries like China will democratise as they become richer. And recently, he has shifted his focus to how culture and institutions – rather than democracy as such – impact growth.

Building on Acemoglu, a February 2025 paper confirmed that a link between democracy and income historically exists, but is not linear.

In poorer countries, according to the study, initial income boosts often come with a dip in freedoms, while it’s only once a certain threshold of prosperity is reached that their democracy starts to improve.

Why is this the case? One of the paper’s co-authors, Petros Sekeris from the TBS business school in Toulouse, thinks the wealthier people become, the more willing they are to “work less and spend more time in the street, online, or in groups, pressuring the government and helping the country democratise”. But causation is hard to pin down. The model stands up with economic data, Sekeris explains, but he doesn’t have hard facts about what precisely sparks citizens to push for democracy – or not. For example, the rise of new media has obvious impacts on democracy, he says, but it’s not captured in the data.

It’s Not (Just) the Economy!

This points to a key downside in such statistical analyses of democracy and GDP: they can’t always account for other historical shifts, whether it’s TikTok, climate change, immigration – or figures like Donald Trump.

Famously, the current US president doesn’t tend to follow conventional logic; neither does he distinguish greatly between democracies and non-democracies. His tariffs, for example, didn’t just stump economists – they also hit democracies like Switzerland, Canada, India, and Brazil particularly hard.

Some researchers have thus been cautioning against over-emphasising material factors in explaining political change. For example, economic dissatisfaction is often blamed for the “backsliding” of democracy in recent years. But data doesn’t always support this. As Thomas Carothers and Brendan Hartnett write in the Journal of Democracy, sometimes individual politicians, like Trump, consciously decide to take their country down a certain path.

In the end, they say, “leaders still matter”.

Meanwhile the question of if – or why – democracies are under-performing might be less important than the narrative itself. In Europe, citizen satisfaction with politics is often lower than objective measures of how things are.

“When you keep reading things online like ‘democracies are not doing well’, this is very influential,” says Matías Bianchi from the Asuntos del Sur think tank in Buenos Aires.

The narrative of weak and inefficient democracies is stoked by countries like Russia and China, which are happy to see their rivals “eroding from within”, Bianchi says. The same dynamic is seen in the Global South, where “people are increasingly unhappy with the delivery of democracy, which is one reason they opt for populists or authoritarians who promise results – like Javier Milei.”

Switzerland – A Model Pupil, But Why?

As for Switzerland, it’s not immune to the new global shifts – nor to Trump’s tariffs, which economists reckon could shrink the country’s GDP by 0.7% in a worst-case scenario. Yet even then, Switzerland would be rich. It’s also highly competitive (see chart) and enjoys extensive direct democratic rights.

What’s behind its prosperity – politics or economic choices?

“Taxes and location factors have a huge influence on Swiss economic performance,” says Marco Portmann from the IWP institute at the University of Lucerne. “But the important thing is that they result from sound political decisions – and this has a lot to do with institutions.” In the Swiss case, Portmann explains, the combination of direct democracy, federalism, and balanced electoral rules make for a slow but consensual system which produces the “legal and regulatory stability that is vital for business”.

Direct democracy, via referendums and people’s initiatives, lends popular legitimacy to decisions while also having a generally sobering effect on state spending, says Portmann; he cites the famous 2012 rejection of six weeks’ paid holiday as an example. Of course, voters won’t always make rational choices, especially since they rely on getting sound information. But Portmann notes that policymakers, too, can misallocate funds – especially in times of surplus – while autocracies aren’t always efficient either.

“It seems that hardly a week goes by in which you don’t hear about a potential bubble in China,” he says.

Neither do autocracies fare better when it comes to the gap between rich and poor (see chart) – an issue often cited as fuelling citizen anger, and which has exploded globally, including in the US.

Switzerland has meanwhile managed to keep inequality – at least when it comes to income rather than wealth – relatively in check in the long run.

But while this might be a benefit to its stability, it’s not clear that democracy played a role: Portmann’s IWP colleague Melanie Häner-Müller told Swissinfo a few years ago that the country’s flexible labour market and dual system of education and training are the main factors.

A Geopolitical Affair

In the end, data-driven analyses of prosperity and growth might only be able to explain so much. With the geopolitical situation shifting, democracies are simply facing a new reality, according to Eliza Urwin from the Centre on Conflict, Development and Peacebuilding (CCDP) at Geneva’s Graduate Institute.

“The old logic that democracy brought growth and trade brought peace no longer holds,” Urwin says. And rather than a positive promise, democracy is increasingly a geostrategic issue in which competing narratives vie for influence – with the authoritarian story seeing much success in recent years. “Autocracy sells itself by saying an iron fist will bring security and stability; anywhere people feel insecure, this is a powerful argument,” she says.

As such, the two major promises of democracy – that it can bring stability and prosperity – have taken a hit. For now, arguments in its favour are often hard-nosed. In Urwin’s case, the focus is clear: in June, she was in Brussels to present a paper to NATO officials, among others.

The topic: democracy as “essential to European and transatlantic security”.

Edited by Reto Gysi von Wartburg/gw