At a Local Election That Captured the Public Imagination

This is the latest in a regular feature, “Where in the World Is Bruno Kaufmann?”

Each piece offers the democracy reporter-and-supporter’s reflections from his global travels on behalf of Swiss Broadcasting, the Swiss Democracy Foundation, and the Global Forum on Modern Direct Democracy.

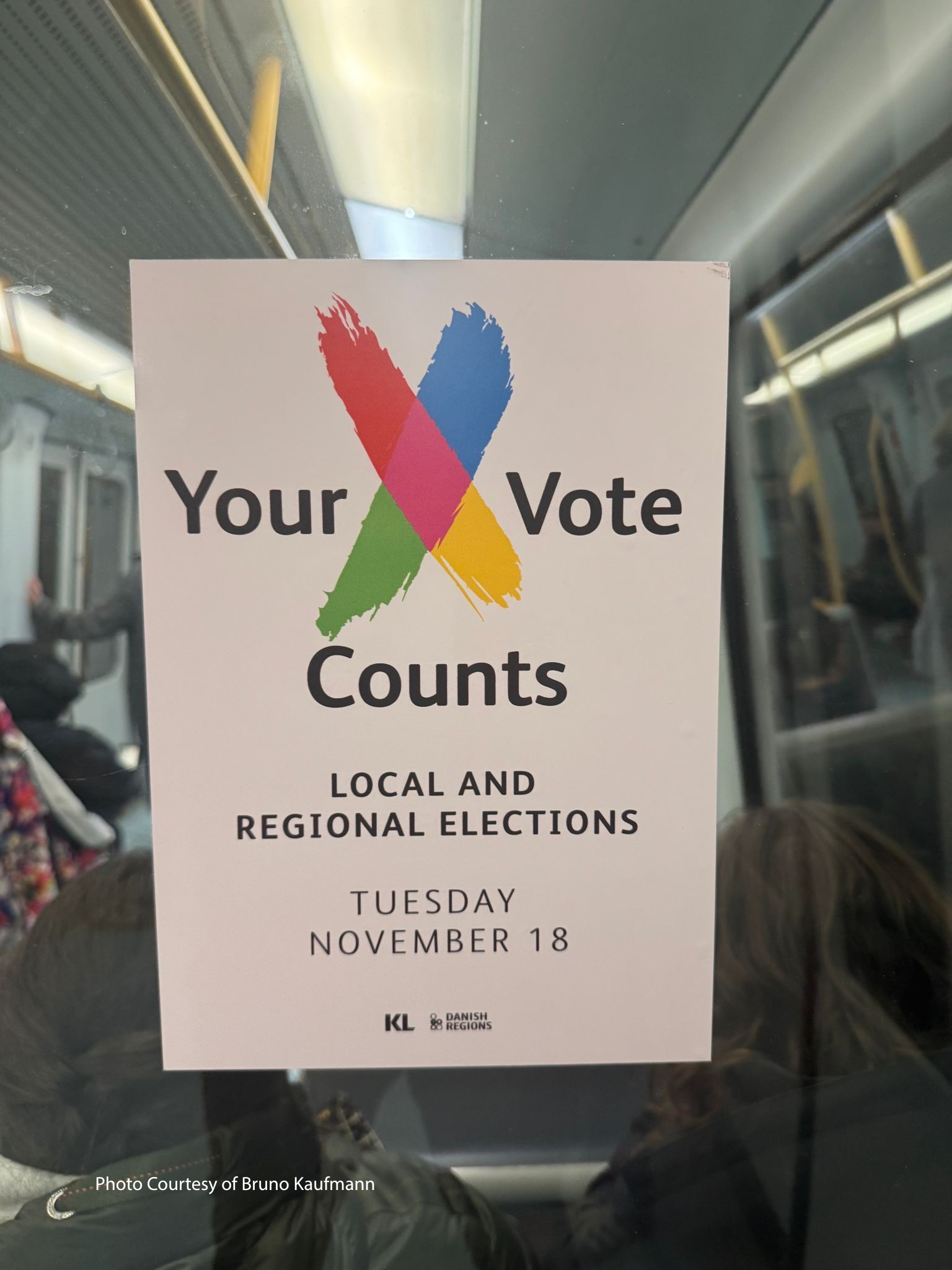

I was in Copenhagen on November 18 to follow the local elections. It was the same date for local elections in 98 municipalities across Denmark.

I’ve never experienced a local election getting so much attention.

Especially in Denmark.

Usually, the national election is the one when people and the media pay attention.

The result was historic. Copenhagen is now, for the first time in 100 years, not being run by the Social Democrats. The party lost heavily not only in Copenhagen but all over the country.

It’s a consequence of the Social Democrats and their government going to the right in recent years under the Prime Minister, Mette Frederiksen. She invested a lot of time in getting people on the right into her coalition, and that created space on the left.

In the Copenhagen local election, that space on the left was filled by green and left parties, which got almost 50 percent, while the Social Democrats got just a little bit more than 10 percent.

But the most interesting story was not the results, but rather how people really engaged in the local elections.

It was an energizing moment for local democracy in Denmark. The media gave it a lot of attention. Every night on TV, you would see local debates between the parties, and talk about the local agenda and policy. And people learned how much the local level influences their life, especially in housing, health care, transportation, and child care.

It showed how Danish local politics worked.

The election night was interesting too. As soon as the results are ready, party representatives (and the media) don’t go to the parties to celebrate the victory and complain about their defeat. They all go together to the city hall to negotiate power.

As soon as the result is clear, the party representatives have to meet. And they are not supposed to leave the city hall before they agree on a government.

Who is the mayor? Who runs which department?

The negotiations are not easy. Almost everywhere in Danish politics, no one has a majority. Almost everywhere, up to 10 parties have seats. So, it’s not easy to figure things out. In some places, they have been negotiating at city hall for 10 days as I write this. The media waits outside.

It’s fascinating. So much energy goes into the talks. There are intrigues and deals. In Copenhagen, for instance, the leader of the Social Democrats wanted to stay in government and keep this position, and she invited people, other parties to her office in city hall. But over the first two or three hours of talks, all the party leaders eventually left the Social Democrats' office for the Green Party office. And they got a Green mayor.

What’s the lesson?

Here is one. International politics have taken so much attention in Denmark—and the prime minister has been extremely focused on those politics, which have to do with Europe, NATO, Greenland, with the US. And at the national level, she was also focused on politics, using this traffic signal strategy. Which means red (welfare), yellow (hard immigration policies) and green (for the climate issue).

But while politicians and party people were interested in international politics, and dividing up their own posts and managing their own interests, the people often felt forgotten.

The election showed that people wanted more focus on their lives and on the local level. It was also a message to Social Democrats who want to stay in power:

People want solutions, not promises.

On election day, I was in the Democracy Garage, an organization and democracy space in Copenhagen. The team there has really extended their activities. There are 10 or 12 staff members, and they do a lot of democracy education. In Denmark, you’re seeing more of a non-governmental consciousness—that you have to be active and do things for democracy, and not just let political parties and government run the game.

This idea of democracy centers, like Democracy Garage, is extending all over Denmark.

I think this is a moment for Denmark to reinvent their democracy. In many ways, the old certainties are gone. Denmark is not this Euro-skeptic country anymore. They are really in the heart of Europe now. And, of course, their old friend, the U.S., is now an enemy.

And this creates lots of new ways of thinking about what the country can be.