The Enduring Example of LA's Azusa Street Revival

This story was produced and published by Zócalo Public Square.

What if the key to understanding American democracy lies not in marble hallways but in a dusty Los Angeles horse stable, where a one-eyed Black preacher gathered people to pray?

In the spring of 1906, William J. Seymour, the son of formerly enslaved parents, launched a revival on Azusa Street in downtown Los Angeles. That converted livery stable quickly became the birthplace of modern Pentecostalism and one of the most racially integrated religious gatherings in American history. Seymour preached a message on divine healing and sanctification to a crowd of Black, white, Asian, and Latino worshippers that defied the logic of segregation. As parishioners fell to their knees in prayer, speaking in tongues, something profound happened:

They practiced a kind of democracy that few had ever seen.

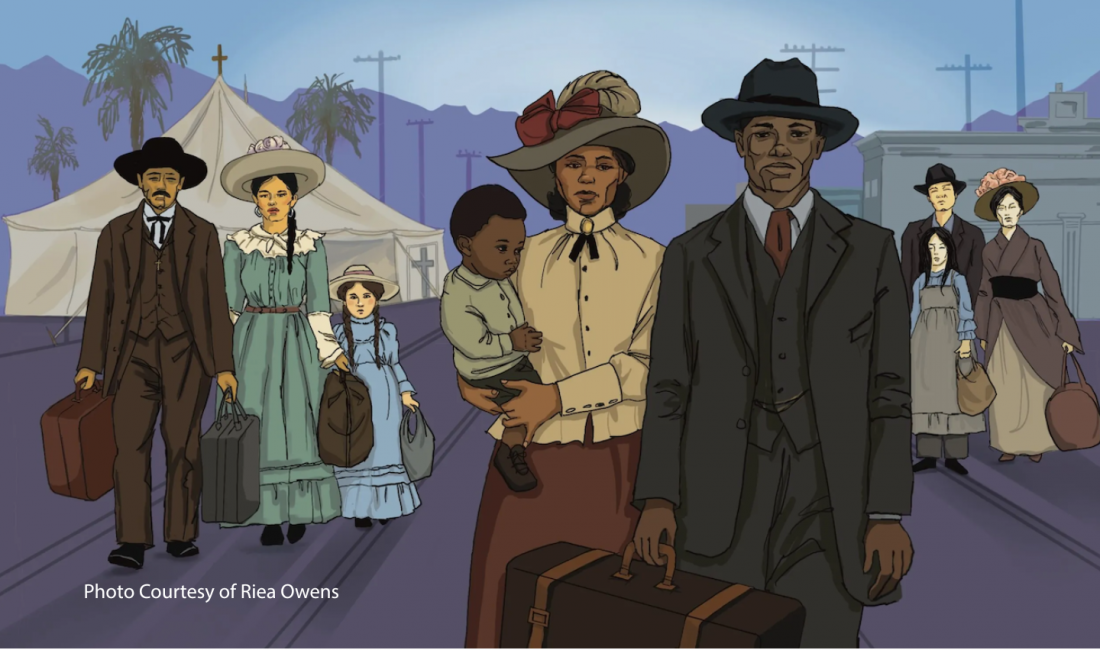

The story of Azusa is just one episode in a much larger, and often overlooked, chapter in American history. Most Americans assume the Constitution will protect our rights and secure our freedoms. But for some, the system has never lived up to its promise. During the early 20th century, thousands of African Americans fled the racial segregation and violence of the Jim Crow South and migrated westward, remaking cities like Los Angeles. They brought with them more than suitcases and Bibles. They carried a moral vision shaped by the Black freedom struggle, the Exodus story, and a belief that although American democracy had failed them, it could be made real. As we face a renewed crisis of democracy today, the new communities they built—which modeled belonging and critiqued exclusion—offer a lesson.

This democratic vision was not born in California—it was forged earlier, in the crucible of slavery, the broken promises of Reconstruction, and the federally sanctioned oppression and racialized violence of Jim Crow. And yet, in the face of brutality, many did not fret or cower—they moved. First to Kansas and Oklahoma during the 1879 Exoduster movement, and then to northern and midwestern cities at the start of the Great Migration in 1910—places like Chicago, Detroit, and Philadelphia. Some journeyed even farther west, to California.

Many understood this westward movement as a sacred journey. The biblical story of Exodus became a central narrative: Black southerners saw themselves as a people delivered from bondage and tasked with building a promised land. They did not wait for America to live up to its ideals. Instead, they reimagined democracy through a lens of faith.

Migration itself became a form of protest and possibility.

Nowhere was this more evident than in Los Angeles, where the physical and spiritual landscape offered room to build anew. When Seymour arrived there from Jim Crow Texas in 1906, he found a city in flux, with Black migrants, Mexican laborers, white spiritual seekers, Chinese railroad workers, and German and Polish Jews all navigating new lives.

The young preacher’s message of spiritual revelation met this moment with radical clarity. Unlike traditional, segregated Protestant churches of the era, which emphasized formal preaching and rigid hierarchies, Pentecostalism emphasized direct and experiential encounters with the Holy Spirit as described in the Book of Acts. At Azusa Street, interracial worship modeled how people could commune together.

Under Seymour’s leadership, Azusa became a space where racial hierarchy collapsed, at least momentarily. Women could preach. Black pastors baptized white immigrants. Worshippers spoke in Spanish and Yiddish.

The Los Angeles Times mocked it as chaos. But Seymour saw it as a divine intervention. What made Azusa powerful was the insistence that spiritual authority did not follow the logics of race, gender, or class. Dignity and power could be shared, not hoarded.

Seymour was not alone; other Black religious leaders in early-20th-century Los Angeles embraced a similar vision. Rev. Prince C. Allen, known for his spectacular revivals and interracial gatherings, spoke of a church that would “gobble all the others,” suggesting that Pentecostalism’s spiritual fire could consume racism at its roots.

Rev. J. Gordon McPherson, called “Black Billy Sunday,” preached to multiracial crowds across Southern California.

“This is the way it will be on the judgement day,” he declared. “The white millionaire of Pasadena is likely to find himself standing at the bar of God by the side of his colored houseman, and they will be on exactly the same footing. If we do a little of the mixing now, it won’t be so surprising.”

In tent meetings, street revivals, and mass baptisms at Echo Park Lake, these leaders turned public space into spiritual commons. These were not politicians. But they were democratic visionaries. Black churches became training grounds for civic life. They offered food, shelter, and job opportunities. More than that, they offered belonging. In a city that treated Black migrants as invisible, these congregations made people feel seen.

In the decades that followed, Black churches built upon this work, imagining democracy as a lived experience and a shared moral project. As the city grew, these congregations continued modeling multiracial, grassroots democracy—outpacing other civic institutions by offering women leadership roles, redistributing labor and housing resources, and helping Black Angelenos launch businesses at a time when lenders denied them access to capital. Members of L.A.’s People’s Independent Church of Christ, founded by Black migrants in 1915, explicitly referred to their ideology as “democratic religion.” The church’s second pastor, Rev. Clayton D. Russell, helped create the Negro Victory Committee in 1941, to protest racial discrimination in Los Angeles’ defense industry. The church also led on other civil rights issues, sending a delegation to the 1943 Mexican American Conference to declare Black Angelenos’ solidarity with the wrongly convicted Mexican American teenagers in the now-infamous 1942 Sleepy Lagoon murder case.

“We cannot have Victory abroad without the fullest support from the people at home,” Russell wrote at the time, in the Black newspaper the California Eagle. “We must stop the persecution of minorities to have a united people.”

Russell understood that the struggle for Black freedom was—and would always be—bound up with the struggles of other communities of color. For him, religious conviction was a public ethic, one that called believers to fight for justice in the world around them. Russell’s wartime push for unity led Black leaders to reimagine Los Angeles—not as a city divided by strict racial lines, but as a multiracial civic experiment still in the making.

It’s easy to romanticize migration as a one-time journey. But for African Americans in the early 20th century, migration was an ongoing practice of rebuilding. It required courage, but also imagination. To move to Los Angeles was to believe that something different was possible. Although they were not immigrants in the traditional sense, many African Americans who left the South for the U.S. West in this period called themselves “emigrants.” That word mattered.

It signaled a shift in self-understanding. No longer tethered to the brutal legacy of slavery, they were people in motion searching for a place to redefine their relationship to the nation. Charlotta Bass, who arrived in Los Angeles in 1910 and later became editor and owner of the California Eagle, described stepping into the city as entering a “new country.” That was the scale of their hope.

Azusa Street did not last forever; eventually, the revival fractured along racial lines. But its legacy endures, as we confront a democracy in distress. We live in a moment when immigrants are demonized, voting rights are being eroded, and public trust is fragile. But the lesson of early Black migration is that democracy has always been made and remade by ordinary people, practiced in churches, kitchen conversations, street corners, and classrooms. It lives wherever people gather to resist the hierarchies that divide us. If we want to save American democracy, we should heed the lessons of the people who had faith, and courage, to begin again.

This piece publishes as part of “What Can Become of Us?,” a collaboration between the Stanford Institute for Advancing Just Societies and Zócalo Public Square.